Illustration by Sean Nyffeler of Popcorn Noises fame

[This was originally a three-part series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3.]

We spend a lot of time gobbling up media. We want to do fun stuff, and we want to do stuff on the cheap. Such is life in a stagnant economy. One of my go-to, quick and dirty ways to choose one option over the others is to figure out the cost per hour for each of my options, and then choose the one with the lowest cost per hour.

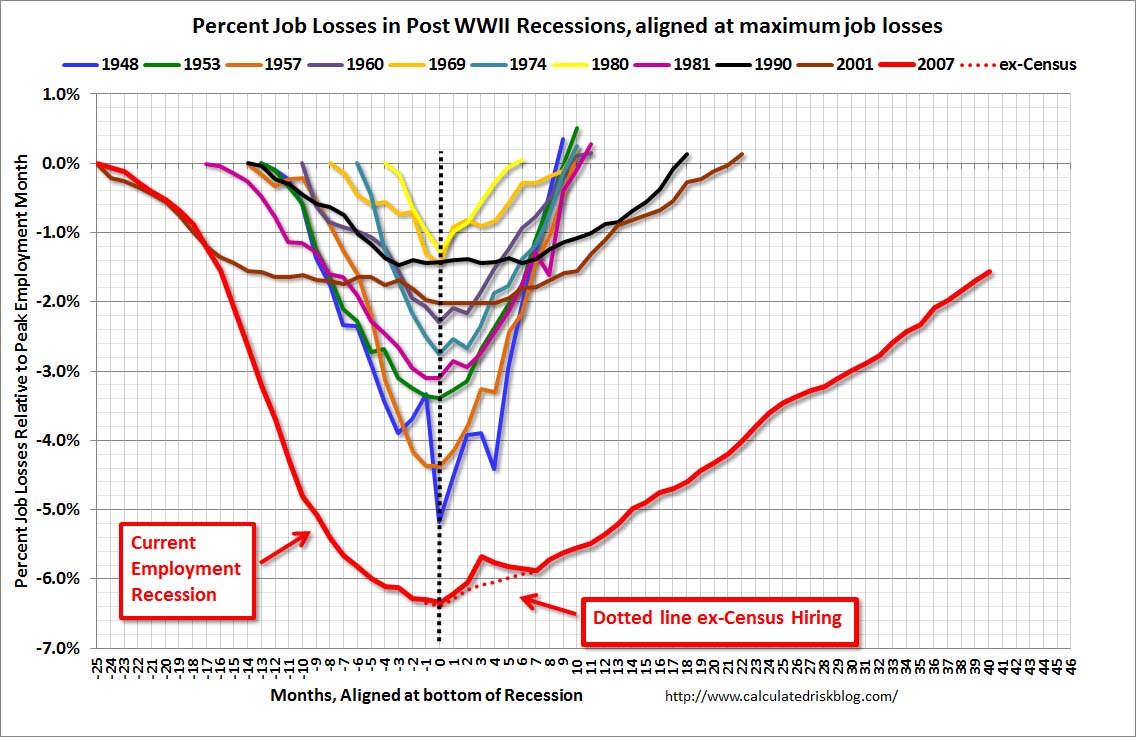

Here’s a quick summary of the cost to consume different types of media, shown in ascending worst-case dollars per hour :

- Podcast – free – As long as I have iTunes and an internet connection, I can get just about any podcast free of charge.

- News online – free – Yeah, the NYT has a pay wall now, but they don’t have any news I can’t get for free somewhere else.

- Video games – $.03 to $1.25 – Angry Birds, Madden, NCAA: they all take so long they end up being really cheap by the time we’re through with them.

- Books – $.25 to $2 – This one obviously depends how fast you read, but a good old paperback can go a long way on short change.

- MP3 albums – $.3 to $4 – The trick with MP3s is to find them on sale. The Amazon MP3 store runs sales all the time.

- Movies – $.50 to $5 – Movies tend to run the gamut because there are so many ways to get them. Prices vary pretty widely from Redbox to IMAX.

Almost any way I slice it, movies are one of the most expensive pieces of the entertainment pie. Looking back at my personal habits over time , it’s pretty obvious that I’ve been moving to cheaper and cheaper options over time. This wasn’t a conscious decision, but I have been purposely reducing my spending over the past few years, and I’ve obviously accomplished that by buying cheaper media.

Consuming media isn’t just about being entertained as cheaply as possible ; I want quality entertainment. It’s not as simple as just consuming some type of media–I also have to figure out which examples of a given type of media to choose. If I’m listening to podcasts, how do I decide which ones? How do I find good books to read? How do I decide which movies to see in the theatre and which ones to rent? How do I know which ones to avoid altogether? The easy answer is recommendations. The trickier answer is expectations.

Recommendations

Over the past decade, recommendations have gone from an informal give and take to a very sophisticated marketing tool, employed by giant companies to boost sales. Amazon, Netflix, Apple’s App Store and many other companies rely on recommendations to keep customers coming back for more. “Recommendation Engines” have become a closely guarded secret and a competitive advantage designed keep customers from switching to a competitor. I’ve bought hundreds of items on Amazon, and I like the recommendations it provides based on my previous purchases. If I start shopping at another online vendor, I’ll have to start over from scratch. That would be a lot of work, so I’m likely to stay with Amazon for quite a while unless a competitor offers something significantly better or Amazon totally drops the ball.

Many of my social interactions revolve around either sharing recommendations or comparing opinions on different media. For as long as I can remember, I’ve frequently asked friends what they’re into: “Seen any good movies lately?” or “Have you heard the new Girl Talk? How is it?” For almost any kind of media, I have at least one friend who’s practically on speed dial in case I need new recommendations.

I also make a lot of recommendations. I love it when a friend tweets, “Looking for some good books to read this summer. Any suggestions?” It takes me a few questions to figure out what kind of stuff they like, but once I zero in on their preferences I can usually recommend several titles that I can almost guarantee they’ll like. The same goes for music, movies, podcasts and TV shows. Part of being a maven is that I’ve always got a solid cache of information ready to share if someone’s careless enough to open the door for me.

Expectations

The flip-side to recommendations is the expectations they create. If a friend of mine, let’s call him Morris, has successfully recommended 10 documentaries to me without any stinkers, then I expect his next doc recommendation to be a good one. If another friend, let’s call him Les, has recommended five documentaries for me, and all of them have been terrible, then I expect his next recommendation to be terrible and I’ll eventually just stop listening to his recommendations altogether. If Morris and Les both make recommendations to me at the same time, I can safely choose Morris’ recommendations because I expect them to be better. With each recommendation Morris and Les make, I can reevaluate their recommendations as a whole to determine how much weight I’ll give to either recommender in the future.

This is also true for recommendation engines like those at Amazon and Netflix. If Amazon starts recommending stuff that I hate, I’ll take that into account in the future and begin lowering my expectations for the stuff they recommend. Eventually I’ll just stop buying stuff they recommend, and that may remove the exit barrier I described earlier so that I’m comfortable going to another company and starting over from scratch.

There’s a feedback loop of recommendations and expectations. With each new good recommendation I get from a friend, the higher my future expectations will be that the stuff he recommends is worth my time and money. With each bad recommendation I get from a friend, the lower my future expectations will be that the stuff he recommends is worth my time and money. Eventually, I will learn to anticipate exactly how accurate my friends’ recommendations will be.

Recommendations and expectations are part of an adaptive framework wherein each future recommendation carries the weight of all previous recommendations. This feedback loop is only useful if I compare my actual experience to my actual expectations.

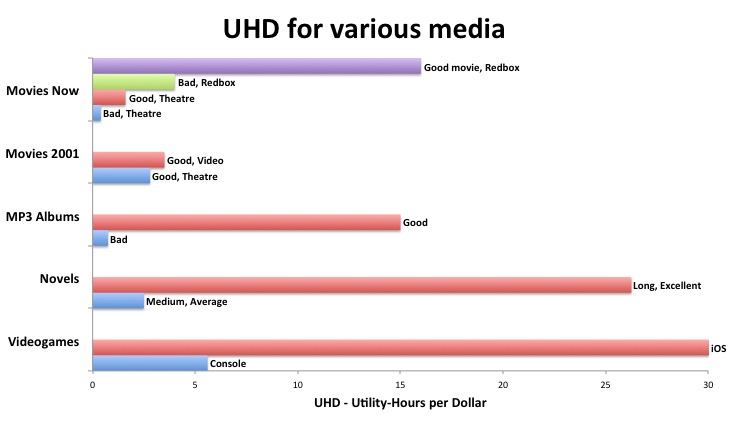

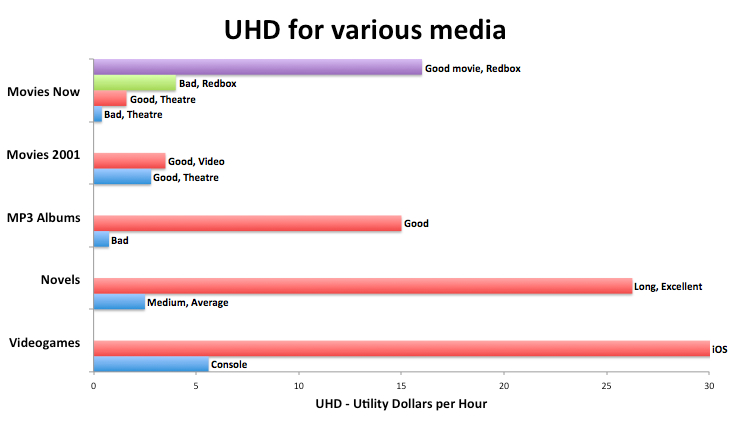

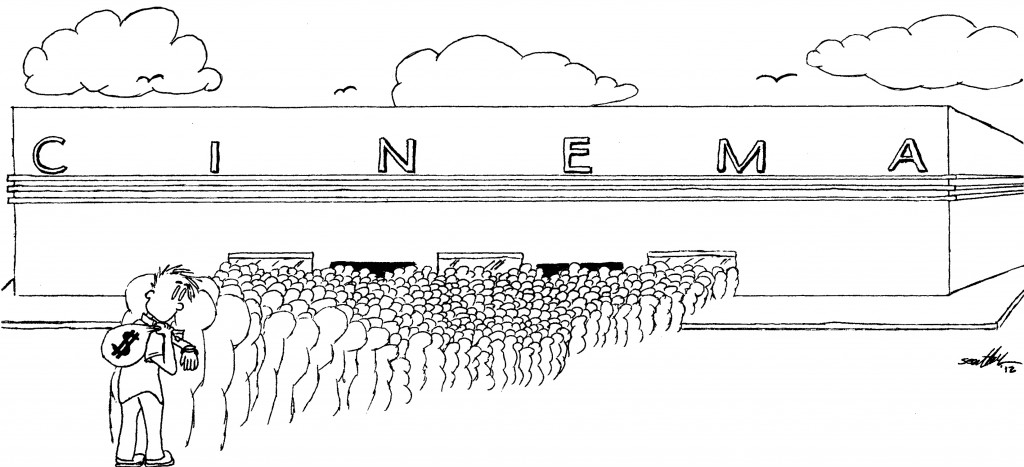

Utility-Hours Per Dollar

Before I can compare outcomes to expectations, I need a way to objectively measure my general satisfaction with any particular piece of media. Dollars per hour is a good metric to figure out the cost of consuming media, especially if my biggest concern is keeping a budget. It helps me measure efficiency. I might say, “Well, I’ve got three bucks left in my entertainment budget this month. I might as well stretch it as far as I can. What’re my options that are three bucks or cheaper and provide the most entertainment time?” But I’m not just looking for any old media–I want the good stuff. I need a way to account for both efficiency and the relative enjoyment offered by something. Enter this new thing I’m creating called “Utility-Hours per Dollar” (UHD) . The UHD allows me to normalize things so that I can compare apples to apples. Yes, going to see a movie in the theatre is really expensive ($5 per hour), but what if it’s the most fun thing I could possibly do with five bucks? That has to count for something, right? Sure it does.

I calculate UHD like this:

- Find the absolute cost (in dollars) of the media I’m looking to buy.

- Estimate how long (in hours) it will take to consume.

- Subjectively determine its utility on a 10-point scale (1 is for awful stuff, 10 is for incredible stuff).

- Multiply the utility number by the number of hours.

- Divide that number by the cost, rounded to the next highest dollar. For free stuff, use $1 (not $0).

For those who like a tidy formula, here it is:

- UHD = (Utility * Hours) / Dollars

That’s it. Here are a couple examples :

- A really bad movie at the theatre would be $10, last 2 hours and provide a utility of 2:

- 2 utils * 2 hours = 4 util-hours

- 4 util-hours / $10 = .4 UHD

- A pretty good album that I buy on Amazon for $8 might give me 20 solid hours of listening at 6 utils:

- 6 utils * 20 hours = 120 util-hours

- 120 util-hours / $8 = 15 UHD

A UHD near zero sucks. A UHD that ends up in the double digits is pretty good. Stuff with a UHD in the mid-to-high double digits is pretty great. Using this metric, I can figure out my most cost effective, enjoyable option for entertainment.

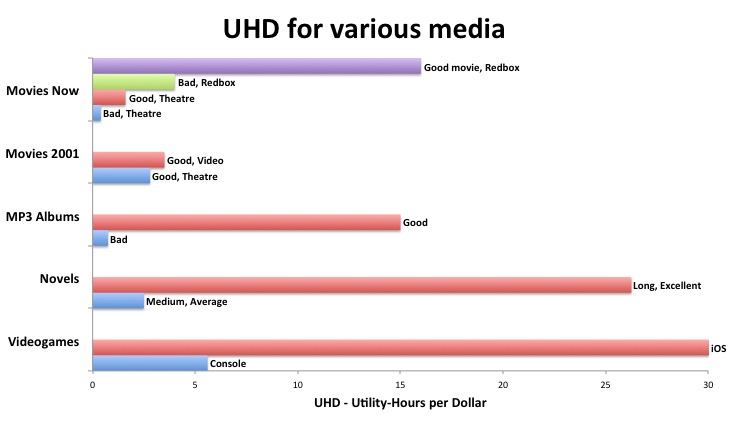

Our trusty UHD chart–we’ll see this again later

UHD isn’t as esoteric as it seems

I realize that, at first, UHD just seems like a wonky way to describe something that’s already obvious and intuitive. But it actually has real-world applications, especially when it comes to understanding our intuitive-but-not-easily-explained preferences for stuff.

For example, UHD helps me understand why it took me a little while to move from CDs to downloading MP3s . Initially, the cost of an MP3 album (on iTunes, for example) was pretty close to the CD and Apple was using DRM . My concern was that I wouldn’t “own” the music if I paid for the MP3s. The result was that the utility of the MP3s was less than that of the CD, even though it was the same music at the same cost. Since the cost was similar, and the hours of entertainment would be the same, the difference in utility made the UHD for CDs higher than MP3s. Eventually, Amazon started offering DRM-free downloads and cheaper prices, shifting the UHD for MP3 downloads ahead of CDs. That’s when I made the switch to MP3 downloads . Of course, I didn’t actually do a conscious UHD calculation one day and say, “Ah ha! The UHD for MP3s is finally greater than it is for CDs! Time to make the switch!” But that’s basically what happened. The same process is happening for me with eBooks right now.

A brief, anecdotal history of cinema

The shift from CDs to MP3s, or from physical books to eBooks is interesting to me. But what’s really interesting to me is the persistence of movie theaters despite cheaper, very similar movie-watching options. Fifty years ago, the only real option for seeing a movie was to go to the movie theatre. This was great for movie companies because they could charge high prices since they were basically the only game in town. The UHD calculation wasn’t really useful for deciding how to watch a movie because it wasn’t so much a matter of comparing different movie-viewing options as just deciding whether it was worth it to spend the money on a movie or not. If it wasn’t, you just had to find something else to do.

Then technology started changing, opening the door for the home theatre experience. First, VHS started enabling people to watch movies at home en masse. Hi-fi began morphing into fancier surround sound setups whose cost was dropping so that more and more people could buy them. LaserDisc came and went. Then DVD took hold and made the home-viewing experience even better.

A sidebar into UHD for movies at the turn of the century

Ten years ago, we really had two options for watching a movie (without owning it). We could either go to the theatre or rent it at Blockbuster. Let’s run through the UHD calculations real quick, just to get an idea of the difference in UHD for these two options at that time:

- A good movie as a “New Release” rental was about $4 (-ish), lasted 2 hours and provided a utility of 6:

- 6 utils * 2 hours = 12 util-hours

- 12 util-hours / $4 = 3 UHD

- The same good movie in the theatre would have been about $5, lasted 2 hours and provided a utility of about 7 (slightly higher since it was in the theatre):

- 7 utils * 2 hours = 14 util-hours

- 14 util-hours / $5 = 2.8 UHD

So the UHD for renting versus going to the theatre was really close even as recently as 2000. They were close enough that there was a real decision to be made: Spend $5 and go to the theatre or spend $4 and stay home? We would often decide what to do based on the number of people in a group (if there were four of us, we could just split the rental for a buck a piece; if there were two of us, then why not just pay for the movie in the theatre?) and our willingness to sneak snacks into the theatre.

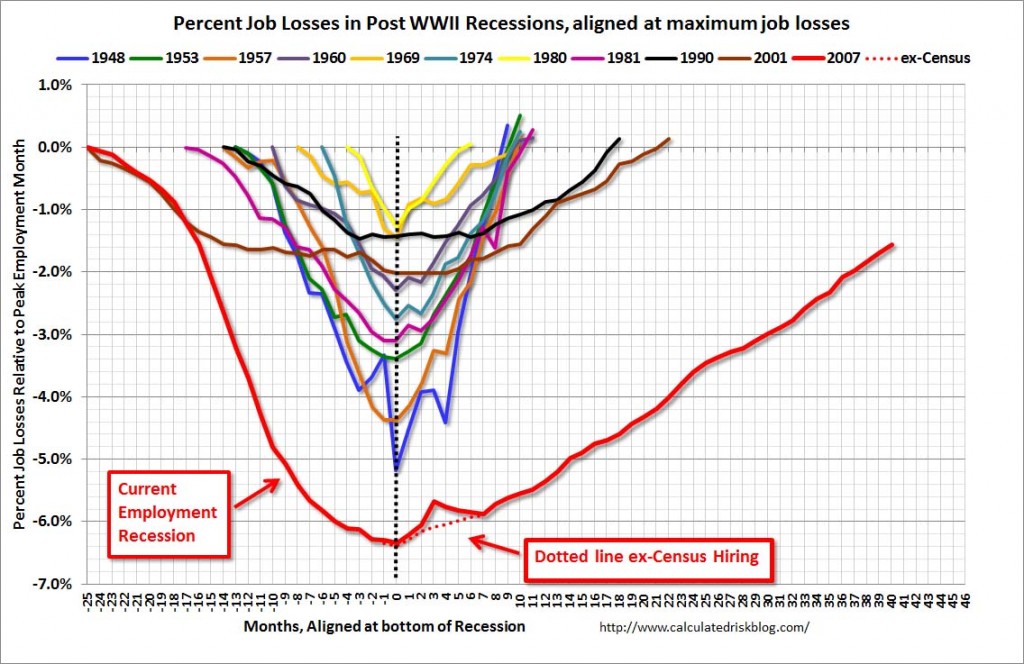

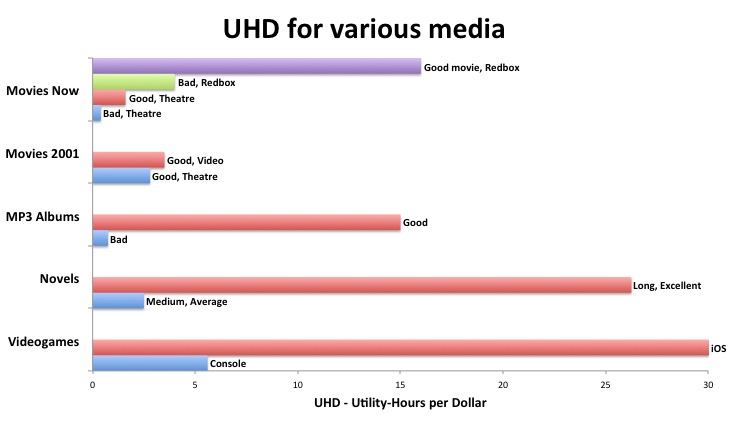

Our trusty UHD chart from earlier

Snap back to reality

A lot has happened over the past 10 years or so. Netflix popped up, HD-DVD lost the war to Blu-Ray, streaming video became better and better, Blockbuster got crushed, and DVD rentals have gotten cheaper and cheaper. There are options now, options that just weren’t available when movie theaters first became a big deal. Not only are there options, but there are cheap options that rival the actual movie-going experience. And yet, movie ticket prices have been steadily increasing over time.

Let’s look at one more sample UHD calculation:

- A really bad movie that I waited to watch on Redbox DVD would be $1, last 2 hours and provide a utility of 2 :

- 2 utils * 2 hours = 4 util-hours

- 4 util-hours / $1 = 4 UHD

As we saw earlier, watching the bad movie in the theatre gives .4 (that’s point-four) UHD. Watching the same bad movie on DVD gives 4 UHD. Watching the bad movie on DVD is 10 times “better” than watching it in the theatre, and all of this difference is accounted for by the difference in cost. “But wait!”, you say, “What if I enjoy watching movies more in the theatre?! I really like going to the theatre!” Ok, fine. How much better would the movie have to be in the theatre to make up for the difference in UHD?

Some people will want to go to the most extreme case first, so let’s just go straight there. Let’s say that the bad movie moves from 4 utils to 10 utils just because I enjoy going to the theatre so much. It only jumps to 2 UHD (still half of the 4 UHD if I wait to watch the bad movie on Redbox DVD). “That doesn’t make any sense!” My counter would be, “So you’re saying there’s no way any movie can be better than the bad movie in the theatre? What if you go see a good movie in the theater?” Since the 1-10 scale is a subjective scale, I have to leave room above the bad movie for less-bad movies. Either that or I have to slide my Redbox DVD experience down to a 1 or something. If I move the theatre experience up to a 10 and move the Redbox DVD experience down to a 1, then I get the same result for both options: 2 UHD.

The present, seemingly uncrossable gulf between UHD for going to the movies and watching them at home is due to super high, sticky movie prices and much, much cheaper alternatives for watching movies at home. This has created such a big gap in cost that watching movies in the theatre is just that much more expensive, ruining their UHD relative to the very-similar experience of watching movies at home now.

Going to see movies in the theatre is expensive. I realize some people will say, “But your formula is just wrong. It weights the cost too much.” Using the UHD calculation as-is, it’s hard to see many situations where it would be better to go to the theatre than to watch the flick at home. It’s possible that I’m weighting cost too heavily, but I think the real problem is that movie theaters are just way too expensive now because we have more, better options. There really is that much of a difference in cost between movie theaters and rentals.

Movie Expectations – A bizarre special case?

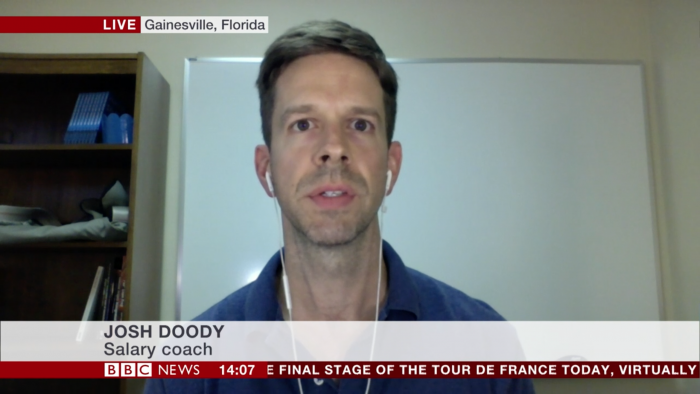

And yet, new releases continue to set box office records as people go to the theatre in droves. At the same time, the movie theaters are much more expensive than the alternatives, and the quality of the movies released has been consistent (or at least not improving enough to justify the growing gap between theatre prices and the alternatives). What gives? If I’m right that waiting for the movie on DVD is almost always better than going to the theatre, then why do so many people continue going to see movies in the theatre? Why did I go see three movies in the theatre this summer?

I’ve overheard this sentiment several times recently: “That movie wasn’t that bad. I just went into it with no expectations and it turned out ok. I’ve decided I just won’t have expectations for movies because I end up over-hyping them and when they don’t meet my expectations I feel ripped off.” So the idea is that movies are often bad because we expect them to be good, or at least because we expect them to be better than they actually are. To solve this problem, we play mind games with ourselves, intentionally under-hyping a movie so that when we go see it and it’s just an ok movie, it exceeds our deflated expectations.

At first, I saw the wisdom in this tactic. If we get really good at lowering our expectations, almost any movie will be a success, at least inasmuch as it will exceed our expectations. That way, we can pretty much guarantee that when we pony up $10 for a ticket and another $10 for concessions, we won’t be let down.

The more I think about this, the more ridiculous the idea seems. We don’t lower our expectations for music, books or TV shows, do we? So why do we do that with movies? Of all our options, movies are one of the most expensive options we have. Why would we trick ourselves into doing something super expensive that we don’t really enjoy that much?

But this one goes to 11.

What we’re doing when we go see movies with deflated expectations is trying to trick ourselves into accepting the lower utility of the movie and ignoring the greater cost. Let’s say we go see the same bad movie we’ve talked about already, but we have “no expectations”, meaning we essentially expect the movie to be about 1 util of entertainment. That way, when we go to the movie and it’s 4 utils, we exceeded expectations! We practically created three utils out of thin air! Um, ok. But the problem is that the movie itself is still only 4 utils. It has to be because we have to put every other movie we’ve ever seen on the same scale. We can’t artificially inflate the number of utils to, say, 5 because what happens to those other movies that really were a 5? This also reduces the perceived value of a 10 because we’re watering all of our other movie experiences down. So if we inflate the utility from a 4 to a 5, what we’re really doing is inflating the whole scale. Now it goes to 11. We have created UHD inflation.

A Delightful Food-Poisoning Analogy

It’s as though we have a friend who likes to cook. He says, “Hey everyone! Come over to my place and bring $5. I’ll cook something for all of us to eat. It’ll be delicious!” So we all go over there and bring five bucks. We eat the meal and it’s really freaking terrible. Half of us are disappointed and the other half are left with Oregon Trail flashbacks. A few weeks later, the same friend makes the same offer. We all decide to give it one more shot–maybe he just had a bad night, right?–and we head back over there with our five bucks. Same thing happens. Half of us are disappointed and the other half end up battling the dysentery. A couple weeks later, the same friend makes the same offer again. Would I go? Of course not. But what if I said, “You know what? I’m going back! I’ve learned that I just have to lower my expectations so I can really enjoy the food poisoning! I’m going to just assume it will kill me this time, or at least that it’ll ruin my digestive system for the next few days. It’s going to be terrible! I can’t wait!” I’m tricking myself into paying $5 for the privilege of being food-poisoned by my friend.

Ridiculous, right? How’s that any different than saying, “The trick to movies is that I just lower my expectations as much as possible. If I go in without expectations, I can’t be disappointed!” Well, kind of. But you’ll trick yourself out of $10 and you’ll waste time that you could’ve spent doing something cheaper and better.

What’s going on here?

So why do we trick ourselves into going to see bad movies in the theatre at 10 times the cost of the Redbox DVD? What’s really strange is we don’t do this with other stuff. If anything we tend to inflate our expectations, especially when it comes to music. I’ve heard friends totally pan a new album just because it didn’t live up to their expectations, which were far higher than they should’ve been. This happened with She & Him’s “Volume 2”. Many of my friends said they didn’t like it, and it was just more of the same from She & Him. Well, duh. They’re still She & Him and their first album was awesome. I’d say “Volume 1” was like 8 utils to me. I expected “Volume 2” to be about 8 utils. I think some of my friends expected it to somehow magically be 10 utils. Why? I have no idea. Turns out it was right about 8 utils (maybe slightly less, but it was really close). I ended up enjoying it a lot (and still listen to it regularly), whereas they ended up all disappointed and annoyed. Of course, they just did that to themselves.

So, with music, a lot of my friends do the opposite of this movie theatre trick–they inflate their expectations so they’re artificially disappointed when they hear a new album. This is silly, but at least it makes some kind of sense: If we’re going to mess with expectations, we should manipulate the numbers so we tend to be less satisfied. That way, we’re basically tricking our future selves into spending less money. But this leaves us in an awkward place: we trick our future selves into spending more money on expensive stuff (movies at the theatre), and less money on cheap stuff (music). If we’re going to trick ourselves, we should be tricking ourselves so that we’re less satisfied with expensive stuff and more satisfied with cheaper stuff. At least that way we end up tricking our future selves avoiding the more expensive purchases on stuff we don’t like anyway. The UHD for music is almost always higher than it is for movies so, if anything, we should tend to “trick” ourselves into consuming more music and fewer movies in order to use our time and money more efficiently by consuming better stuff.

Why do we have it backwards? There could be a few explanations for this. Rather than trying to make sure we spend our money as efficiently as possible, we’re more focused on justifying expensive movies because they’re a cultural staple:

“Did you see the new X-Men movie?”

“No, I’m waiting for it on DVD.”

“Lame-o! Hey everybody! This guy’s super lame!”

It’s not cool to wait to watch movies on DVD. If I show up at the water cooler on Monday morning after a big release , nobody wants to hear anything I say if it starts with, “Well, I’m waiting for that one to be available on Netflix streaming.”

Sometimes there are benefits to seeing a movie in the theatre, especially action flicks. But we can account for that by bumping the utils for the movie just a little bit. Maybe X-Men on DVD is 6 utils, but X-Men in the theatre is 8. Ok, but does that justify the 10-times-higher price tag? The UHD sure doesn’t think so.

Conspiracy Theory!

There’s also some clever marketing going on by the movie studios. Most of the movies made are crap. We tend to remember good things more than bad, but most movies are really, really bad. This is easily confirmed by just browsing Netflix for movies . Some friends and I recently spent about two hours scrolling and scanning through Netflix to find a movie to watch. We ended up just re-watching Arrested Development Season 1. The issue wasn’t a lack of options, it was a lack of good options. There just weren’t any. We looked at hundreds of movies and all of them were terrible. If we used movie studios’ previous product as an indicator of future quality, we’d almost always opt not to go see movies in the theatre because there’s just too much risk that the movie will be crap and we’ll waste $10. Waiting for the DVD gives us more time to get recommendations from other people who have seen it so we can decide whether it’s even worth seeing on DVD.

But movie studios have cleverly convinced us that we should set our expectations aside so we can enjoy the movie-going experience itself. Of course, as discussed earlier, the movie theatre experience isn’t really much different than just watching the movie at home (there are a few exceptions). If we all had the appropriate level of expectations for movies, we would rarely go to the theatre because we would mostly be disappointed. But instead of just saving that cash and doing something with higher UHD, we buy into this idea that we should essentially forget all the crap they’ve fed us previously so that we can enjoy this current experience more.

Positive Reinforcement of Terrible Moviemaking

But it’s actually worse than that. By tricking ourselves into “liking” (and paying for) bad movies, we’re encouraging movie studios to make more bad movies. If I trick myself into paying $10 to see Zookeeper, then I just gave the movie studios $10 and a green light to start production on Zookeeper 2: Flying Poo. Now I have to trick myself into going to see that dud, too?

Not only am I tricking myself into spending a lot of money on a bad movie, but I’m feeding the movie making machine so that it continues to churn out garbage that I have to trick myself into overpaying for in the theatre next time. I’m essentially a recommendation engine whose recommendations are made in dollars. I’m saying, “Movie studios. I recommend that you make Zookeeper 2: Flying Poo! Here’s ten bucks to get you started!” When does it end?

It is ending

In many ways, this phenomenon is ending, if only subtly. There are myriad modern sources of recommendations that are almost forcibly removing our self-imposed myopia. For example, Rotten Tomatoes is a crowd-sourced recommendation engine that is almost impossible to ignore once you know it’s out there.

“Want to go see the new Zookeeper movie?”

“What’d it get on Rotten Tomatoes?”

“Eleven percent.”

“And how did the first one do on Rotten Tomatoes?”

“Fourteen percent.”

“This one is worse than the first one? That’s pretty bad. I’ll pass.”

That’s what saving $10 and two hours sounds like. I have conversations like this one a couple times a month. On the flip-side, I often decide to go see a new movie specifically because Rotten Tomatoes rates it highly. For example, when I was in Vancouver last year, my friends and I went to see Drive because I saw it got something like 90% on Rotten Tomatoes. They had never heard of the movie, and I had only heard a little about it, but the Rotten Tomatoes score pushed me to recommend it to them. We also went to see The Help and Moneyball because of high scores on Rotten Tomatoes. All three movies ended up getting Oscar nominations There were a few other movies that we skipped because the Rotten Tomatoes score was so low.

Recommendations Engines are enabling us to make better decisions and making it more difficult to declare that we’re lowering our expectations to justify a trip to the theatre. It’s a lot easier to lower expectations when there’s some chance that the movie will be good despite the trailer or word-of-mouth buzz it’s been getting. But when thousands of people have already said it’s a bad movie and we know that, then it’s much harder to pretend it might be good.

The trick is that we, as consumers, have to listen to what so many other people are telling us through all the recommendations vehicles that are out there. When we start listening to others’ recommendations, we can set our expectations appropriately to maximize two of our scarcest resources: time and money.

SPECIAL THANKS

I put a lot of work into this piece, but I also got a lot of help from other people. Jason Killingsworth offered his editorial insight and sage advice to help make it better and more readable. Jason was also one of the first bloggers I read, so there’s a nice historical symmetry here. Danny Anderson did the final review before I published, and helped me figure out how to wrap it all up. Sean Nyffeler illustrated the piece (twice, actually: he did a draft, took some notes and re-did the illustration for the published version). Several other people were sounding boards who helped me refine the basic ideas over the past several months. Thanks to everyone who helped make this a better piece.