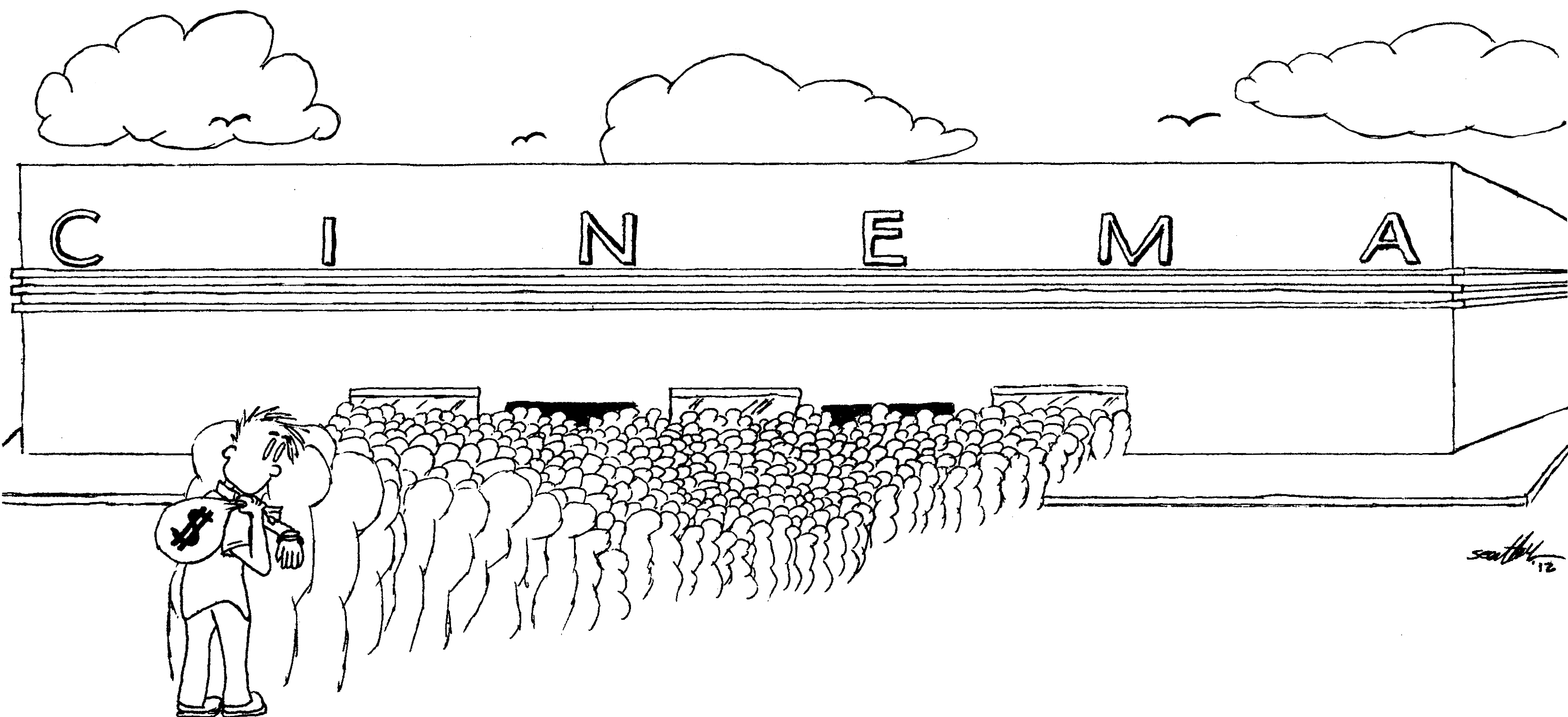

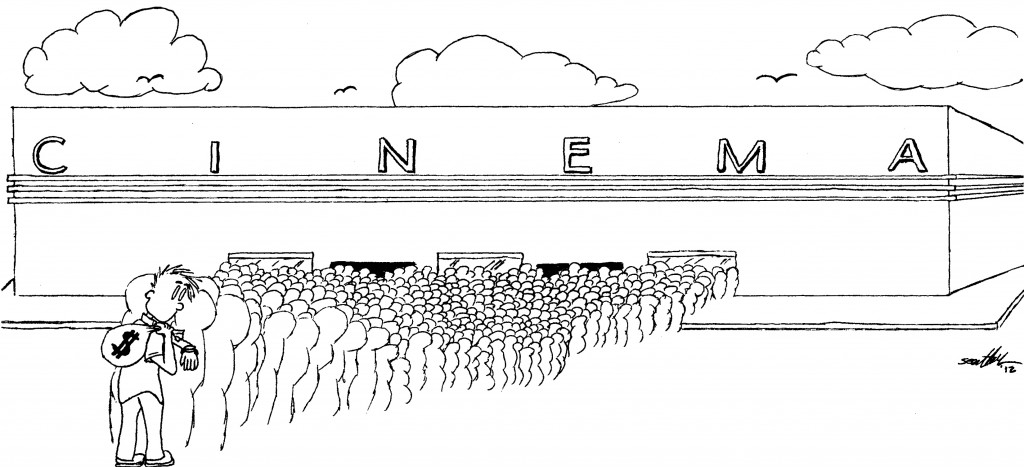

Illustration by Sean Nyffeler of Popcorn Noises fame

PREVIOUSLY, in Part 2: How we all use UHD to decide what to buy, and how we sometimes ignore UHD altogether. [Click here to view the entire piece as a single page.]

But this one goes to 11.

What we’re doing when we go see movies with deflated expectations is trying to trick ourselves into accepting the lower utility of the movie and ignoring the greater cost. Let’s say we go see the same bad movie we’ve talked about already, but we have “no expectations”, meaning we essentially expect the movie to be about 1 util of entertainment. That way, when we go to the movie and it’s 4 utils, we exceeded expectations! We practically created three utils out of thin air! Um, ok. But the problem is that the movie itself is still only 4 utils. It has to be because we have to put every other movie we’ve ever seen on the same scale. We can’t artificially inflate the number of utils to, say, 5 because what happens to those other movies that really were a 5? 1 This also reduces the perceived value of a 10 because we’re watering all of our other movie experiences down. So if we inflate the utility from a 4 to a 5, what we’re really doing is inflating the whole scale. Now it goes to 11. We have created UHD inflation.

A Delightful Food-Poisoning Analogy

It’s as though we have a friend who likes to cook. He says, “Hey everyone! Come over to my place and bring $5. I’ll cook something for all of us to eat. It’ll be delicious!” So we all go over there and bring five bucks. We eat the meal and it’s really freaking terrible. Half of us are disappointed and the other half are left with Oregon Trail flashbacks. A few weeks later, the same friend makes the same offer. We all decide to give it one more shot–maybe he just had a bad night, right?–and we head back over there with our five bucks. Same thing happens. Half of us are disappointed and the other half end up battling the dysentery. A couple weeks later, the same friend makes the same offer again. Would I go? Of course not. But what if I said, “You know what? I’m going back! I’ve learned that I just have to lower my expectations so I can really enjoy the food poisoning! I’m going to just assume it will kill me this time, or at least that it’ll ruin my digestive system for the next few days. It’s going to be terrible! I can’t wait!” I’m tricking myself into paying $5 for the privilege of being food-poisoned by my friend.

Ridiculous, right? How’s that any different than saying, “The trick to movies is that I just lower my expectations as much as possible. If I go in without expectations, I can’t be disappointed!” Well, kind of. But you’ll trick yourself out of $10 and you’ll waste time that you could’ve spent doing something cheaper and better.

What’s going on here?

So why do we trick ourselves into going to see bad movies in the theatre at 10 times the cost of the Redbox DVD? What’s really strange is we don’t do this with other stuff. If anything we tend to inflate our expectations, especially when it comes to music. I’ve heard friends totally pan a new album just because it didn’t live up to their expectations, which were far higher than they should’ve been. This happened with She & Him’s “Volume 2”. Many of my friends said they didn’t like it, and it was just more of the same from She & Him. Well, duh. They’re still She & Him and their first album was awesome. I’d say “Volume 1” was like 8 utils to me. I expected “Volume 2” to be about 8 utils. I think some of my friends expected it to somehow magically be 10 utils. Why? I have no idea. Turns out it was right about 8 utils (maybe slightly less, but it was really close). I ended up enjoying it a lot (and still listen to it regularly), whereas they ended up all disappointed and annoyed. Of course, they just did that to themselves.

So, with music, a lot of my friends do the opposite of this movie theatre trick–they inflate their expectations so they’re artificially disappointed when they hear a new album. 2 This is silly, but at least it makes some kind of sense: If we’re going to mess with expectations, we should manipulate the numbers so we tend to be less satisfied. That way, we’re basically tricking our future selves into spending less money. But this leaves us in an awkward place: we trick our future selves into spending more money on expensive stuff (movies at the theatre), and less money on cheap stuff (music). If we’re going to trick ourselves, we should be tricking ourselves so that we’re less satisfied with expensive stuff and more satisfied with cheaper stuff. At least that way we end up tricking our future selves avoiding the more expensive purchases on stuff we don’t like anyway. The UHD for music is almost always higher than it is for movies so, if anything, we should tend to “trick” ourselves into consuming more music and fewer movies in order to use our time and money more efficiently by consuming better stuff.

Why do we have it backwards? There could be a few explanations for this. Rather than trying to make sure we spend our money as efficiently as possible, we’re more focused on justifying expensive movies because they’re a cultural staple:

“Did you see the new X-Men movie?”

“No, I’m waiting for it on DVD.”

“Lame-o! Hey everybody! This guy’s super lame!”

It’s not cool to wait to watch movies on DVD. If I show up at the water cooler on Monday morning after a big release 3, nobody wants to hear anything I say if it starts with, “Well, I’m waiting for that one to be available on Netflix streaming.”

Sometimes there are benefits to seeing a movie in the theatre, especially action flicks. But we can account for that by bumping the utils for the movie just a little bit. Maybe X-Men on DVD is 6 utils, but X-Men in the theatre is 8. Ok, but does that justify the 10-times-higher price tag? The UHD sure doesn’t think so.

Conspiracy Theory!

There’s also some clever marketing going on by the movie studios. Most of the movies made are crap. We tend to remember good things more than bad, but most movies are really, really bad. This is easily confirmed by just browsing Netflix for movies 4. Some friends and I recently spent about two hours scrolling and scanning through Netflix to find a movie to watch. We ended up just re-watching Arrested Development Season 1. The issue wasn’t a lack of options, it was a lack of good options. There just weren’t any. We looked at hundreds of movies and all of them were terrible. If we used movie studios’ previous product as an indicator of future quality, we’d almost always opt not to go see movies in the theatre because there’s just too much risk that the movie will be crap and we’ll waste $10. Waiting for the DVD gives us more time to get recommendations from other people who have seen it so we can decide whether it’s even worth seeing on DVD.

But movie studios have cleverly convinced us that we should set our expectations aside so we can enjoy the movie-going experience itself. 5 Of course, as discussed earlier, the movie theatre experience isn’t really much different than just watching the movie at home (there are a few exceptions). If we all had the appropriate level of expectations for movies, we would rarely go to the theatre because we would mostly be disappointed. But instead of just saving that cash and doing something with higher UHD, we buy into this idea that we should essentially forget all the crap they’ve fed us previously so that we can enjoy this current experience more.

Positive Reinforcement of Terrible Moviemaking

But it’s actually worse than that. By tricking ourselves into “liking” (and paying for) bad movies, we’re encouraging movie studios to make more bad movies. If I trick myself into paying $10 to see Zookeeper, then I just gave the movie studios $10 and a green light to start production on Zookeeper 2: Flying Poo. Now I have to trick myself into going to see that dud, too?

Not only am I tricking myself into spending a lot of money on a bad movie, but I’m feeding the movie making machine so that it continues to churn out garbage that I have to trick myself into overpaying for in the theatre next time. I’m essentially a recommendation engine whose recommendations are made in dollars. I’m saying, “Movie studios. I recommend that you make Zookeeper 2: Flying Poo! Here’s ten bucks to get you started!” When does it end?

It is ending

In many ways, this phenomenon is ending, if only subtly. There are myriad modern sources of recommendations that are almost forcibly removing our self-imposed myopia. For example, Rotten Tomatoes is a crowd-sourced recommendation engine that is almost impossible to ignore once you know it’s out there.

“Want to go see the new Zookeeper movie?”

“What’d it get on Rotten Tomatoes?”

“Eleven percent.”

“And how did the first one do on Rotten Tomatoes?”

“Fourteen percent.”

“This one is worse than the first one? That’s pretty bad. I’ll pass.”

That’s what saving $10 and two hours sounds like. I have conversations like this one a couple times a month. On the flip-side, I often decide to go see a new movie specifically because Rotten Tomatoes rates it highly. For example, when I was in Vancouver last year, my friends and I went to see Drive because I saw it got something like 90% on Rotten Tomatoes. They had never heard of the movie, and I had only heard a little about it, but the Rotten Tomatoes score pushed me to recommend it to them. We also went to see The Help and Moneyball because of high scores on Rotten Tomatoes. All three movies ended up getting Oscar nominations 6 There were a few other movies that we skipped because the Rotten Tomatoes score was so low.

Recommendations Engines are enabling us to make better decisions and making it more difficult to declare that we’re lowering our expectations to justify a trip to the theatre. It’s a lot easier to lower expectations when there’s some chance that the movie will be good despite the trailer or word-of-mouth buzz it’s been getting. But when thousands of people have already said it’s a bad movie and we know that, then it’s much harder to pretend it might be good.

The trick is that we, as consumers, have to listen to what so many other people are telling us through all the recommendations vehicles that are out there. When we start listening to others’ recommendations, we can set our expectations appropriately to maximize two of our scarcest resources: time and money.

SPECIAL THANKS

I put a lot of work into this piece, but I also got a lot of help from other people. Jason Killingsworth offered his editorial insight and sage advice to help make it better and more readable. Jason was also one of the first bloggers I read, so there’s a nice historical symmetry here. Danny Anderson did the final review before I published, and helped me figure out how to wrap it all up. Sean Nyffeler illustrated the piece (twice, actually: he did a draft, took some notes and re-did the illustration for the published version). Several other people were sounding boards who helped me refine the basic ideas over the past several months. Thanks to everyone who helped make this a better piece.

- This could apply to anything where we artificially inflate our subjective evaluation of something on a bounded scale. University grade inflation is a good example of this. Ok, so everyone gets all As and Bs… how do we find the really good students now? And where did all the mediocre and bad students go? We’re just watering down the accomplishments of the really good students through illusory grade inflation, and we’re hurting ourselves because when it comes time to find a really good student, we can’t find them. They’re all buried in a pile of mediocre and bad students, who are all reveling in their fake good grades. Put differently, we’re taking what should be a sort of “normal” curve centered around “C” (which is supposed to mean “average”, right?) and shifting the center of the curve upward. {a}

{a} Shifting the center upward isn’t the only issue. The main issue is that the center of the curve is being shifted upward to a fixed boundary {i} at “A”. So we end up with a glut of students with grades around A/B and nobody below them. That’s not helpful to students, professors, or potential employers.

{i} I guess we can sort of cheat here since “A+” exists now. But how far can we go? “A++”? “AA”?

- This obviously seems a lot like a general hipster thing, but I’m already like 10,000 words into this sucker and I don’t feel like trying to explain how hipsters trick themselves into being ambivalent about everything they experience. “They silently overhype everything so they can publicly pan everything.” That seems like a sufficient explanation. {a}

{a} I know I’m pretty much safe here because hipsters don’t care enough to read long articles, and they especially don’t care enough to read footnotes. Even if they did care that much, they definitely don’t care enough to bother responding in any way. They’re totally above that nonsense. Fight the establishment!, etc.

- This would be doubly awkward because I don’t have a job {a}, so I would be just showing up at a random water cooler in someone’s office, looking to talk about a new movie that I don’t plan to see until it drops on Netflix streaming. This seems like a great way to mess with people. Challenge accepted!

{a} HA! Now you know how long ago I started writing this piece! Still, I’m not cutting this footnote. So there.

- Yeah, I guess it’s possible this could be a result of sampling bias, viz. Netflix’ streaming selection isn’t representative of the set of all movies as a whole. But we weren’t looking for new movies, just movies. Since we were looking for any movie to watch (unconstrained by release date), we should have been browsing a set representative of all (or most) previous movies that have been released, including good movies. I guess it’s possible that somehow Netflix’ streaming selection is mostly bad movies (meaning that the good movies aren’t available there), but that seems unlikely.

- Eg, the Oscars, Golden Globes, AFI Top 100. These are all marketing as much as anything else. Much of the marketing is designed to just get us to watch movies, but much of it is focused on the “unique” experience of going to the theatre.

- Granted, Oscar nominations aren’t a guarantee that a movie is good, but they’re a pretty good indicator.