Illustration by Sean Nyffeler of Popcorn Noises fame

We spend a lot of time gobbling up media. We want to do fun stuff, and we want to do stuff on the cheap. Such is life in a stagnant economy. One of my go-to, quick and dirty ways to choose one option over the others is to figure out the cost per hour for each of my options, and then choose the one with the lowest cost per hour. 1

Here’s a quick summary of the cost to consume different types of media, shown in ascending worst-case dollars per hour 2 3:

- Podcast – free – As long as I have iTunes and an internet connection, I can get just about any podcast free of charge.

- News online – free – Yeah, the NYT has a pay wall now, but they don’t have any news I can’t get for free somewhere else.

- Video games – $.03 to $1.25 – Angry Birds, Madden, NCAA: they all take so long they end up being really cheap by the time we’re through with them.

- Books – $.25 to $2 – This one obviously depends how fast you read, but a good old paperback can go a long way on short change.

- MP3 albums – $.3 to $4 – The trick with MP3s is to find them on sale. The Amazon MP3 store runs sales all the time.

- Movies – $.50 to $5 – Movies tend to run the gamut because there are so many ways to get them. Prices vary pretty widely from Redbox to IMAX.

Almost any way I slice it, movies are one of the most expensive pieces of the entertainment pie. Looking back at my personal habits over time 4, it’s pretty obvious that I’ve been moving to cheaper and cheaper options over time. This wasn’t a conscious decision, but I have been purposely reducing my spending over the past few years, and I’ve obviously accomplished that by buying cheaper media.

Consuming media isn’t just about being entertained as cheaply as possible 5; I want quality entertainment. It’s not as simple as just consuming some type of media–I also have to figure out which examples of a given type of media to choose. If I’m listening to podcasts, how do I decide which ones? How do I find good books to read? How do I decide which movies to see in the theatre and which ones to rent? How do I know which ones to avoid altogether? The easy answer is recommendations. The trickier answer is expectations.

Recommendations

Over the past decade, recommendations 6 have gone from an informal give and take to a very sophisticated marketing tool, employed by giant companies to boost sales. Amazon, Netflix, Apple’s App Store and many other companies rely on recommendations to keep customers coming back for more. “Recommendation Engines” have become a closely guarded secret and a competitive advantage designed keep customers from switching to a competitor. I’ve bought hundreds of items on Amazon, and I like the recommendations it provides based on my previous purchases. If I start shopping at another online vendor, I’ll have to start over from scratch to get new recommendations. That would be a lot of work, so I’m likely to stay with Amazon for quite a while unless a competitor offers something significantly better or Amazon totally drops the ball.

Many of my social interactions revolve around either sharing recommendations or comparing opinions on different media. For as long as I can remember, I’ve frequently asked friends what they’re into: “Seen any good movies lately?” or “Have you heard the new Girl Talk? How is it?” For almost any kind of media, I have at least one friend who’s practically on speed dial in case I need new recommendations.

I also make a lot of recommendations. I love it when a friend tweets, “Looking for some good books to read this summer. Any suggestions?” It takes me a few questions to figure out what kind of stuff they like, but once I zero in on their preferences I can usually recommend several titles that I can almost guarantee they’ll like. The same goes for music, movies, podcasts and TV shows. Part of being a maven 7 is that I’ve always got a solid cache of information ready to share if someone’s careless enough to open the door for me.

Expectations

The flip-side to recommendations is the expectations they create. If a friend of mine, let’s call him Morris, has successfully recommended 10 documentaries to me without any stinkers, then I expect his next doc recommendation to be a good one. If another friend, let’s call him Les, has recommended five documentaries for me, and all of them have been terrible, then I expect his next recommendation to be terrible and I’ll eventually just stop listening to his recommendations altogether. If Morris and Les both make recommendations to me at the same time, I can safely choose Morris’ recommendations because I expect them to be better. With each recommendation Morris and Les make, I can reevaluate their recommendations as a whole to determine how much weight I’ll give to either recommender in the future.

This is also true for recommendation engines like those at Amazon and Netflix. If Amazon starts recommending stuff that I hate, I’ll take that into account in the future and begin lowering my expectations for the stuff they recommend. Eventually I’ll just stop buying stuff they recommend, and that may remove the exit barrier I described earlier so that I’m comfortable going to another company and starting over from scratch.

There’s a feedback loop of recommendations and expectations. With each new good recommendation I get from a friend, the higher my future expectations will be that the stuff he recommends is worth my time and money. With each bad recommendation I get from a friend, the lower my future expectations will be that the stuff he recommends is worth my time and money. Eventually, I will learn to anticipate exactly how accurate my friends’ recommendations will be.

Recommendations and expectations are part of an adaptive framework wherein each future recommendation carries the weight of all previous recommendations. This feedback loop is only useful if I compare my actual experience to my actual expectations. 8

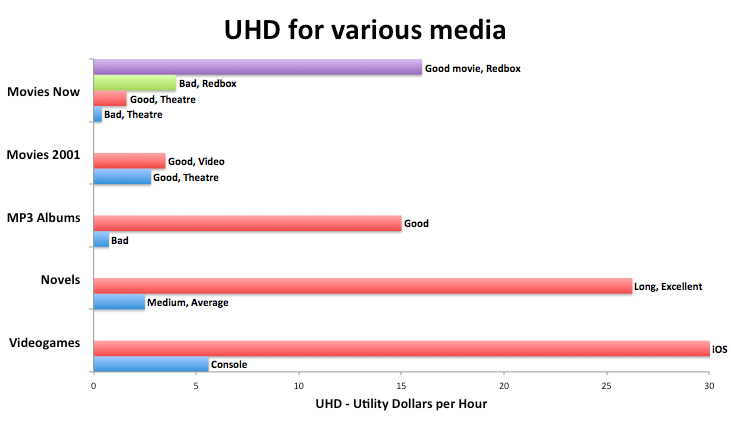

Utility-Hours Per Dollar

Before I can compare outcomes to expectations, I need a way to objectively measure my general satisfaction with any particular piece of media. Dollars per hour is a good metric to figure out the cost of consuming media, especially if my biggest concern is keeping a budget. It helps me measure efficiency. I might say, “Well, I’ve got three bucks left in my entertainment budget this month. I might as well stretch it as far as I can. What’re my options that are three bucks or cheaper and provide the most entertainment time?” But I’m not just looking for any old media–I want the good stuff. I need a way to account for both efficiency and the relative enjoyment offered by something. Enter this new thing I’m creating called “Utility-Hours per Dollar” (UHD) 9. The UHD allows me to normalize things so that I can compare apples to apples. Yes, going to see a movie in the theatre is really expensive ($5 per hour), but what if it’s the most fun thing I could possibly do with five bucks? That has to count for something, right? Sure it does.

I calculate UHD like this:

- Find the absolute cost (in dollars) of the media I’m looking to buy.

- Estimate how long (in hours) it will take to consume. 10

- Subjectively determine its utility 11on a 10-point scale (1 is for awful stuff, 10 is for incredible stuff).

- Multiply the utility number by the number of hours.

- Divide that number by the cost, rounded to the next highest dollar. For free stuff, use $1 (not $0). 12 13

For those who like a tidy formula, here it is:

- UHD = (Utility * Hours) / Dollars

That’s it. Here are a couple examples 14:

- A really bad movie at the theatre would be $10, last 2 hours and provide a utility of 2:

- 2 utils * 2 hours = 4 util-hours

- 4 util-hours / $10 = .4 UHD

- A pretty good album that I buy on Amazon for $8 might give me 20 solid hours of listening at 6 utils:

- 6 utils * 20 hours = 120 util-hours

- 120 util-hours / $8 = 15 UHD

A UHD near zero sucks. A UHD that ends up in the double digits is pretty good. Stuff with a UHD in the mid-to-high double digits is pretty great. Using this metric, I can figure out my most cost effective, enjoyable option for entertainment.

Our trusty UHD chart–we’ll see this again later

UP NEXT, in Part 2: How we all use UHD to decide what to buy, and how we sometimes ignore UHD altogether. [Click here to view the entire piece as a single page.]

- I see you rolling your eyes. Don’t judge me. You do this too.

- I tend to break down costs into dollars per hour of entertainment (I also do this with stuff like shoes and clothes, only in dollars per day {a}). There’s a lot of free entertainment–podcasts, most news, blogs–for $0 an hour. Books are a pretty good value: I paid $12 for my copy of Infinite Jest, and probably got 40 or 50 hours of entertainment at like $.25 an hour (it helps that I’m a slow reader). To be fair, I should include the normal case where I’d pay $12 for a paperback and get six hours of entertainment at $2 an hour. MP3 albums are a decent value: if I pay $8 for an album on Amazon and it’s a good album, I might listen to it 20 or 30 times at about $.30 an hour. If the album’s no good (which rarely happens thanks to previews and friends’ recommendations), I could end up paying $4 an hour if I only listen to it twice. Video games used to be a pretty decent value: $50 for a console game that would yield 30 to 50 hours is somewhere around $1.25 an hour. Of course nowadays I can get Angry Birds for $.99, giving me 35 hours (and counting) of entertainment at about $.03 an hour {b}. Redbox DVDs are a really good value: $1 for two hours of entertainment, or $.50 an hour. Watching a movie in the theatre is about the worst possible dollar-per-hour value: $10 for two hours of entertainment works out to five bucks an hour, and that’s assuming I don’t buy concessions.

{a} If you wonder why I’m wearing the same old shoes I’ve been wearing every day for a couple years, it’s because I’m trying to get down to a nickel a day on those suckers.

{b} This isn’t where I’m going here, but I’m impressed at how consistently innovation and disruptive technologies make things cheaper and cheaper. Nintendo is feeling a lot of pressure from smartphones, especially in the portable gaming business. Why pay $249 for a Nintendo 3DS, plus $30 or so for each game when I can just pay $230 for an iPod touch and get excellent games for a buck? Never mind that iPod touch isn’t just a portable game system.

- Yeah, yeah, yeah. I know there are costs associated with these things (like in order to browse online news, I have to have a laptop or something), but I’m just talking about the cost of the actual media to keep things simple.

- I go through phases where some things are more interesting than others. This year, I’ve listened to podcasts a few hours a day, and I’ve been reading more and more blogs. The last couple years, I listened to ridiculous amounts of music. Before that, I went through a phase where I was watching movies like it was my job. I’m always reading at least three books.

- At least not under normal circumstances. There are times when simply passing time as cheaply as possible is the most important factor. While I’m unemployed, I skew toward the cheaper stuff with less concern about how good that stuff is. Of course, I’d like to get good stuff cheap, but since I can’t afford to pay more, I end up going cheap and hoping it also happens to be good. Normally, I’d look for a combination of good and cheap, allowing myself to spend a little more to get more “good” for less “cheap”.

- Recommendations are really a signal (the term is used a lot in economics and marketing, but I first heard it when I was boning up on my game theory). A signal is just a way for one party to convey information about a thing to another party. Luxury car makers signal quality by showing rich-looking older dudes riding around in really sleek cars in isolated settings, implying (or explicitly stating) that the car is of a quality consummate with rich people who want to be comfortable and feel separate from (better than?) the rest of society. Lite beer commercials signal fun or carefree-ness.

So recommendations qua signals have been around forever. What’s unique about recommendations in this context is that they’re essentially third-party signals, not signals being sent directly from the provider of the thing. Amazon recommends stuff to me based on what other people like me have bought {a}, so the manufacturer isn’t sending me signals, Amazon is sending me signals based on other Amazon shoppers’ experiences. This form of signaling isn’t per se new, but its ubiquity is a new thing. {b}

{a} There are actually a couple kinds of recommendations happening at Amazon. There are recommendations that Amazon makes directly (“Others who bought this book also bought these other books.”), but I also get implicit recommendations on specific items by looking at the aggregated user ratings for the item. “That coffee maker has an average of 4.5 stars, so I’ll get that one since I don’t know anything about any of them.” So Amazon signals based on other users’ purchase history. And Amazon users signal based on their own experiences with individual products. These two things combined are what I’m referring to as Amazon’s “recommendation engine”. {i}

{i} Since you’re still following… This is an example of market efficiencies improving as more information becomes available. Ten years ago, if I needed a coffee maker, I would’ve gone to a brick and mortar store, stood in the “Kitchen Appliances” aisle and stared at the coffee makers for like 20 minutes before finally just grabbing a familiar name brand in my price range. I would be wondering, “Which of these is the best one? Where can I get the most bang for my buck?” If I was really diligent, I could go get a copy of Consumer Reports and dig around for information about different brands and models and all that. But that would take a lot of effort that probably wouldn’t be justified for a $20 purchase. This is pretty inefficient since it’s a time-intensive process, I don’t actually know how good the coffee maker is, and I don’t know whether it’s priced appropriately. Now, I’d just log onto Amazon, search “Coffee Maker”, and probably buy the highest-rated one in my price range. The whole process would take about five minutes and I’d know I’m probably getting the most bang for my buck. That’s a much more efficient market, directing my “investment” to the item that is most likely to meet my needs.

{b} In a meta twist to typical third-party signaling (like word of mouth), some companies are starting to simulate third-party signals in their ads. The most recent version of this I’ve seen is the Ford Focus commercials where they ambush “real customers” by telling them they’re going to be interviewed about their experience with the car, and then dump them in a mocked-up press conference that is recorded for TV. Manufacturers are realizing that third-party signals are valuable and have a lot of pull, so they’re trying to simulate that same type of signal in their own commercials. That way, the company isn’t telling us how awesome the product is, but “real customers” are telling us about it.

- Speaking of book recommendations, if you haven’t read Malcom Gladwell’s The Tipping Point, you probably should. To cut to the chase, a “maven” is someone who gathers and distills large amounts of information, and is also able to share that information in a way that people just “get it”. I don’t know much, but the stuff I do know is ready to be shared at the drop of a hat.

- If you know me well, you know that I usually give sort of pessimistic reviews of stuff. Last night, I watched a movie with friends. When it was over, they asked what I thought. “It was pretty entertaining. It started off a little cheesy, but it hit its stride in the middle. I enjoyed it.” This is pretty typical for me–I rarely give a glowing review of a movie. But this is a conscious decision to try to be as realistic as possible and to leave myself room to give good reviews to stuff that’s really good. I don’t want to be that guy that always says, “It was great! What a great movie!” What good is that for anyone else who’s deciding whether to see a movie? My input is almost totally useless if it’s always very positive. If anything, I bias my reviews so that they’re low, giving my good reviews more weight. I’m playing it safe so that if I say something’s good, I know others will perceive it as good. Of course, people who know me already know this, so they temper their expectations accordingly when accounting for my recommendations.

- Yes, I know this isn’t the most scientific (it may not be scientific at all, actually) way to do this, but it’s easy and allows for a quick and dirty way to compare stuff in a pinch. It’s also convenient for me because it helps set up the real point of this piece.

- I’m using this as a proxy for how much entertainment it will provide. This is another quick and dirty estimate since there’s no guarantee that a book that takes 10 hours to read will actually provide 10 hours of entertainment. I don’t want to count “amount of enjoyment” twice, so I’m ignoring the actual amount of enjoyment here so that I can account for it in the more subjective part of the UHD, the Utility.

- Ok, so I’m just sort of cavalierly assuming everyone is comfortable with the concept of “utility”. In a nutshell, utility is the amount of enjoyment we get from consuming one unit of something. The unit of measuring utility is the “util” (a fictitious, arbitrary unit), so my scale of 1-10 is really a scale of 1-10 utils, where 10 is maximum enjoyment. I’d say that eating an apple is about four utils for me, and eating ice cream is between six and 10 utils depending on what kind of ice cream and how long I’ve been eating it {a}. Here is the Wikipedia page for utility. {a} I’m alluding to the so-called “Law of Diminishing Returns” here. If I haven’t had ice cream in a week (a long time for me), and I finally get my fix, that first bite will be like nine utils. The second, third and fourth bites will be like 8.5 utils. Each successive bite will likely be slightly lower on the scale. If I eat enough ice cream in a sitting, I could eventually get to zero utils and then creep into negative territory, where each bite makes me feel worse and worse until I run out or puke. {i} Since you’re reading the footnotes, I might as well go on a sub-sub-tangent, right? So the question is, “When should I stop eating the ice cream?” An easy deciding point would be to keep eating until I’m out of the positive until territory–I would stop eating when each successive bite provides zero utils (or fewer) of satisfaction. But there are other factors to consider: Should I be doing something else right now? How much exercise will I have to do to get rid of all these calories? How expensive is this ice cream? The more ice cream I eat, the less satisfaction I get from each successive bite, but I also set myself up for sacrificing utils in other areas of my life. This can get really, really complicated, but I’ll just go with a really simple possibility. Let’s say the next bite of ice cream would be 4 utils, but the amount of exercise necessary to work off the next bite would be -5 utils (that’s negative utility meaning I really don’t like exercising just to burn calories). So, eating the next bite of ice cream is really a -1 util decision. If the only two factors in each bite of ice cream I eat are (1) the satisfaction of actually eating the ice cream and (2) the negative satisfaction I’ll get when I have to work it off, then I should stop eating ice cream when the combined utility of the next bite and its correlated exercise is zero or less.

- The UHD starts to break down when the cost is less than a dollar because we start dividing by decimals, inflating the UHD to pretty large numbers as we get close to zero. Rounding to the next highest dollar means we’re always working in relatively round numbers and we avoid dividing by zero. We’re trying to figure out how good a movie is, not putting a man on the moon here. I’m also basically assuming that the stuff we’re talking about–movies, music, books, etc.–is somewhere between free and $10-15. Hence the utility scale of 1-10. If we start including stuff like concerts, theme parks and higher-cost activities, it might be better to use a 100-point utility scale. But this is supposed to be simple, right?

- This is way beyond the scope of this post, but I can’t help but wonder what’s on the other side of “zero cost” in this equation. What if the cost is negative (we’re getting paid to consume the media)? What if there’s negative utility (consuming the media actually makes me worse off)? Or what if we’re not even talking about media anymore, but just anything. Some form of this equation could be useful for evaluating job prospects while accounting for both pay and personal satisfaction (utility) in doing a job. It would take some tweaking, but I think it might be useful. Of course, that’s beyond the scope of this post.

- I’m always assuming we’re talking about one person watching a movie. If there are multiple people, then the additional value in renting the movie increases proportionately to the number of people involved. This is because multiple people can chip in to split a rental, but everyone pays full price if the group goes to the theatre. For every person added to the group, the movie theatre gets linearly more expensive according to the formula C*n where “C” is the cost of the movie and “n” is the number of people in the group {a}. While, for every person added to the group, the rental experience gets geometrically cheaper according to the formula C/n {b}. So the examples I’m using are the best case examples if we’re trying to find some reason to go to the theatre.

{a} There may be some economies of scale vis-a-vis snacks with larger groups, though.

{b} “n” is really the number of paying people in the group. There are always some jokers who say, “Yeah, I’ll kick in!”, but then they don’t.

I really enjoy your UHD concept, especially its glaring statements about seeing films in theaters (although I will say that some movies’ UHD is skewed by confounding factors– films like Hugo, Avatar, and even Mission Impossible:Ghost Protocol in IMAX immediately come to mind) versus Redboxing them, as well as the mighty entertainment value of a good book, iOS game, or album. For someone like me who pretty much listens to music constantly –mostly due to studying “constantly,” the UHD of a good album is pretty much unmeasurable. I also recently read through the Hunger Games trilogy, and although they are all quick reads, I was thoroughly entertained for hours on end for a small fee of $20 for all three books. Pretty fascinated to see where the rest of this post goes…