My 2022 Year In Review was very late to publication. In fact, it’s still not published as I write this in early June of 2023, although I plan to publish it before I publish this piece.

Why?

Because it feels bad. The sub-title is “A weird year” and 2022 sure was a weird year.

I want to drill down on one particular aspect of that weirdness: my business turning from boom to bust on a dime, and what I’m doing to try and save it.

DISCLAIMER: This post is bound to get deep into some nitty-gritty detail. If you skip this one, I don’t blame you. But if you want to ride along through a pretty rocky period of uncertainty to see how I make decisions and think through hard problems, keep on reading…

How I got here

First, a brief history of the business. There’s a lot more detail in my annual Year In Review posts, which I’ve been doing since 2015, so if you want lots of detail, check those out. But for now, he’s a high-level summary…

I quit my last day job in September of 2015 as I finished writing Fearless Salary Negotiation. The plan was to publish it, promote it, and live off of the income from it while I built a software business. I quickly realized how foolish my plan was—selling enough books to pay my bills each month would require its own business, which of course needed to be built in addition to the software business I was already building—and that I had to make a choice: Build a business around Fearless Salary Negotiation or go all-in on the software business and hope to get traction before my runway ran out.

I decided that the salary negotiation business was more interesting to me, so that’s the direction I chose. I shut own the software business and went all-in on the salary negotiation business.

When I quit my day job, I had an 18-month runway—enough cash in the bank to pay my bills with no revenue. That might seem like a long time, but a common axiom in the entrepreneurship circles I run in is that it takes about 18 months for any business to really find its stride. So I had the bare minimum runway, on average.

And of course by the time I had the above epiphany and decided to shut down the software business and focus on the Fearless Salary Negotiation business, I had burned about three months of that runway self-publishing and launching the book.

So, for all intents and purposes, I started my business in January 2016 with about 15 months of runway. It grew very slowly and, through trial and error and some careful planning, I managed to find my stride just before my runway ran out. That was May 2017.

Ever since I started the business it has grown every year:

2016: Infinite growth because I started at zero

2017: 150%

2018: 100%

2019: 50%

2020: 15%

2021: 35%

2021 was about 12x the revenue of 2016 and every year showed positive growth (even during the pandemic).

Zooming in on September 2022

Adding to my list above:

2022 (through August): 3%

So basically flat year-over-year, or on pace to be about the same as 2021, which had been my best year ever.

Starting in April 2022, I kept my eye on the local housing market, just to see what was out there. It all started when a friend sent me a link to a really cool house on Zillow, piquing my interest and getting the wheels turning in my mind: “I’ve been in this house—my first house—for a long time. My business is growing and I can definitely afford to upgrade. Why not just see what’s out there?”

I watched the market pretty closely for the next several months and even went to see a few houses, but nothing really caught my eye.

Then I found an amazing house that I immediately felt was the one for me. It was a stretch, but I talked to my wealth manager, accountant, and several smart people to figure out whether it was worth making the move and whether I could really afford it.

The verdict: “Yes, you can afford it. It’s a little more of your monthly spend that the common wisdom says it should be, but your business is healthy and you have no debt, so you’ll be fine. Your disposable income will drop a little bit, but you won’t be strapped for cash and will still be able to do all the stuff you do now. But instead of socking all of the leftover away in the bank, you’ll be spending some of it on a mortgage and upkeep.”

I made an offer, signed a contract, and sent some cash to escrow.

Within a few days, I felt a disturbance in the force. I couldn’t quite put my finger on it, but something seemed a little off about my business. I had been doing the same thing for more than five years so I just knew how the regular rhythms of the business felt. And something felt weird.

I couldn’t even really point to specific stats or data. But, anecdotally, it felt like there was just less inbound interest in working with me all the sudden. In case you don’t know, I should say: My business was built around helping senior engineers and engineering managers who were changing jobs to big tech companies.

Of course now we know that this was the beginning of a recession in big tech. It turns out that my business was a leading indicator of the health of the employment market in that industry.

But at the time, it seemed likely it was just a blip. My business has had cold spells before—in 2019, I had a 12-week stretch without any new clients—and this might just be another cold spell.

So I was under contract for a new house, which would represent a big increase in my monthly spend, and my numbers were based on a business that had grown every year since it began and was on pace to at least match the previous year’s revenue, which would be more than enough to comfortably make the move to the new house. But I also felt like the business might be slowing down.

What to do?

There were two chances to get off the new-house train: During the inspection period, I could essentially back out, get my escrow money back (which was a big chunk of change), and hit reset on the house-buying process; and before I closed, I could back out and eat the escrow money (which was significant, but was also already a sunk cost).

Remember: All I really had was a feeling that something was off. Nothing concrete. If I decided to pull the plug, it would be based almost exclusively on a hunch.

I only had a 10-day inspection period, and everything came up roses. I considered bailing on the house, but decided that 10 days of “something feels funny with my business” just wasn’t enough of a sample size to make such a big decision. I could still take the next few weeks before closing to see how things went and eat the escrow money if I had to.

Onward to closing.

I now had a checklist with three items on it in order to “thread the needle” on this move without drowning:

- Get approved for financing on the new house. The bank was extremely fastidious in this process and sent me a barrage of requests for documents that seemed like it would never end. Although my broker said approval was inevitable, it sure didn’t feel that way.

- Sell my old house for an amount that would let me cover the down payment on the new house and put some cash in the bank as a cushion.

- Hope my business was only temporarily chilly and not entering a major downturn or dying.

The next few weeks were interesting because I was simultaneously neck-deep in the approvals process for financing on a new mortgage and trying to sell my old house and digging deep into the current state of the business to see if I could figure out if there was a problem or if I was just in a short-term cold spell or something.

It was extremely stressful and I would literally wake up in the middle of the night running numbers, asking myself if I could really afford this, and wondering what would happen if I went through with the purchase and my business died.

I called my wealth manager and accountant again: “You sure I can afford this? What if my business falls off a bit?”

“You’re fine.”

Funky math

Making things even more complicated was a funky mathematical situation that I found myself in. I basically had two options:

- If I felt my business might be slowing down for a bit, making my financial situation too dicey to buy the new house, I could just stay put and eat the escrow money (which was a meaningful amount of my cash on hand). That would leave me in a situation where I had not much cash, but also had a still-very-low burn rate which would enable me to make that little bit of remaining cash last quite a while.

- If I felt the business actually wasn’t slowing down or the slowdown would be short-lived (a few months, say), then I could just go through with the purchase. That would mean selling my old house, putting most of the equity toward the down payment on my new house, but also pocketing the remaining equity.

The funky math was as follows: Staying put would actually leave me less time on my runway than buying the new house because I would be able to pocket so much of the equity from selling my old house. My burn rate would be higher at the new house, but my savings would be higher still such that I would have more months of expenses covered.

You may already have noticed a complicating factor here: I had not actually sold my old house and therefore did not know what actual amount of equity would be realized when I sold it. If I sold it.

I had a pretty good idea what my house would sell for—recall, I had been watching the housing market for about six months—so I knew about pretty much every house that went on the market in certain areas and certain price ranges. I had a guess what my old house would sell for, but I couldn’t know that for sure until I actually sold it (or try to).

Selling the old house

This brings us to a new conundrum: Selling my old house to cover the down payment on the new house and (hopefully) generate some additional equity to use as a runway if I actually went through with everything.

I was very fortunate that my Mom had recently sold the house I grew up in and she had enough cash in the bank to cover my downpayment in the short-term and help me avoid a home-sale contingency on my offer on the new house. We are not a wealthy family—this was just fortunate timing, and there’s probably been no other time in my family’s history when someone had this kind of cash just sitting in a checking account, but I digress.

Once I signed the contract on the new house, I began trying to sell my old house. At first, I tried to sell it through my own network. I posted about it on Facebook and my church bulletin board and got a surprising amount of interest right away.

I thought it would be cool to sell to someone I knew since I had worked so hard to make my old house comfortable. For all the people I talked to, I offered it at the same price, which was a few percent below what I thought it would sell for if I put it on the market.

I quickly had someone interested, they visited the house, then visited again a week later, and eventually sent me an offer for the amount I had asked for. It was a cash offer, which was great because it meant I wouldn’t need to worry about all the financing stuff and the associated timeline risk.

Let me pause here for a second since I sort of glossed over something that is important: I was under contract for my new house and needed the equity from the old house for the downpayment (to repay my Mom) and also hoped to have enough left over to put in the bank as a cushion in case my business was slowing down. For this buyer, the process from “anyone want to buy my house?” to “offer in hand” was about three weeks, leaving me about a week or so from my scheduled closing on the new house. This was a tight timeline that had me a little nervous.

It turns out that the potential buyer and I could not agree on terms for the contract, so the deal fell through. I had another offer or two from my network, but they didn’t come to fruition either. Now I’m a week from closing and I do not know if my old house will sell or how much it will sell for.

I thought I knew what my house would fetch on the open market, but I was not sure and now I had a few data points that said, “Someone thought about buying my house for a few percent less than what I think the market value is, but they backed out. Therefore it’s possible I have overestimated the market value of my house.” (Shoutout to all the Bayesians reading this.)

Meanwhile, the Fed was rapidly raising interest rates to fight inflation, thus increasing mortgage rates, which seemed likely to cause the market to cool off a bit. To give you some insight into how fast this happened: When I signed the contract on my new house, I locked in at 5.125% on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage, and by the time these deals to sell my old house fell through, mortgage rates were closer to 7% and rising.

Worst-case scenario would be if the house didn’t sell at all. Then I would not be able to cover the down payment on the new place or have cash in the bank and I would still have a property and a mortgage to take care of in a time when it was unclear how dependable my normally-dependable business income would be.

I hit the big red button: I asked the realtor who sold me my new house if she would help me sell my old house. We got photos, listed it on a Friday, had an open house on a Saturday, had three or four offers on Sunday, had a bidding war on Monday, and I ended up selling my house for … $1,000 more than I thought it would sell for on the open market. Cash.

“All that build-up over like 10 paragraphs and you just end the story like that?” That’s what it literally felt like in real time.

Closing on the new house

Around this time, I was finally approved for financing on the new house. It was a slog, but we got it done.

At least I could check that off the needle-threading list. Now all that remained was actually selling my old house for enough to cover the new house’s downpayment and (hopefully) put some cash in the bank, and hoping my business was still strong.

I was in for the long haul now. Closing for the new house was set, financing was approved, and I had a contract to sell my old house in a timeframe that would work well for the move.

So I had checked one box (financing on the new house) and was on track to check a second box (sell the old house), and was keeping an eye on the business, which seemed to be chilly at the moment (third box).

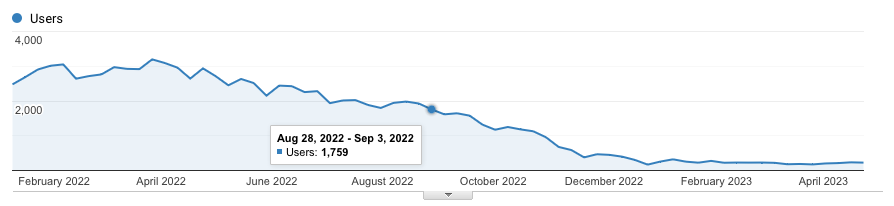

Let’s pause and I’ll show you a graph. This shows weekly visits to the main pages that drive my business (these are all company-specific pages about negotiating job offers and most of my coaching leads come through these pages).

It looks like a pretty normal chart until the marked data point. Typically, around August 1, the summer slowdown starts to abate and the graph heads back up to April-ish levels of traffic. In this way, my business has always been somewhat seasonal, so it’s slower in the Summer months when people are vacationing more and business moves a little bit slower.

The uneasy thing I was feeling at the time was that the traffic to those pages hadn’t returned to pre-summer levels yet, and therefore I had fewer coaching prospects than expected for that time of year.

This is an extremely narrow window to make any real judgements on, but it’s what had given me pause earlier: If this wasn’t just an anomaly and was instead a downturn, what would happen? How long would it last? How bad would it get? And what would the financial ramifications be as I started paying a significantly higher mortgage?

I decided this wasn’t enough evidence to bail on the “buy new house, sell old house” plan, so I moved ahead.

I closed on the new house as scheduled. Then closed on the old house as scheduled. And ended up with a nice cash cushion in the bank, just in case the business was in for a slower-than-normal end of the year.

Covering all my bases

I’m the kind of person who plans for all contingencies. This is both a blessing and a curse. It’s why I was able to plan years out to eventually quit my day job and have an 18-month runway to start something new from scratch. It’s also why I sometimes move slowly and get stuck analyzing and getting input on new ideas rather than just shipping things.

But in this case, it was clear that I needed to make absolutely sure that I did whatever I could to shore up my financial situation just in case the disturbance in the force I felt was a real business downturn.

By the time I closed on my house something was up with big tech. To illustrate this, I just googled “2022 big tech layoffs” and grabbed the first article that mentioned a timeline. Here is is:

Tech layoffs in 2022: A timeline

If you click through to the second page (I’m not sure why the article is paginated), you’ll see that it starts with “Twilio: Sept. 14—850 people”.

This was two weeks into the under-contract period on my new house. Seems small, but it’s something after a huge, years-long hiring boom in big tech.

I needed to hedge my bets, and I had just put a substantial down payment on a new house, so I went looking for options to tap into that equity if I needed to. I started by looking into a HELOC—a line of credit against the equity in my new house—and found that would be the best option. Specifically, I wanted access to a line of credit without having to borrow or pay fees if I didn’t need the cash.

Sure enough, I found a HELOC that was a revolving line of credit that was essentially an interest-payments-only line of credit with a balloon after 10 years. I could borrow, pay only interest, and would have 10 years to pay back the principle. But I didn’t have to borrow or pay any fees if I didn’t want to. It was just a line of credit that I could have in my back pocket if I really needed it.

This was also dicey—I needed to move fast. By the time I moved into my house and the dust settled, I was about two months into a business slowdown and I did not know how long it would be slow. Part of vetting loans is income verification and stuff like that, so I needed to get the HELOC handled before my income dropped off too much. That meant it needed to be done by EOY 2022, giving me only a few weeks to get everything done.

Sure enough, the HELOC was approved and opened before end of year. I had bought and moved into my new house, sold my old house, paid mom back for the down payment money she loaned me, put some cash in the bank as a cushion, and been approved for a backup line of credit that I could use if things got really dire or if I had an unexpected large expense (which is what keeps most homeowners up at night).

For the first time in a few months, I could actually sit back, breathe a sigh of relief and start looking over the business to see what was going on under the hood.

Sliding, sliding, sliding

But I still had that third checkbox: The business needed to return to normal.

It wasn’t looking good.

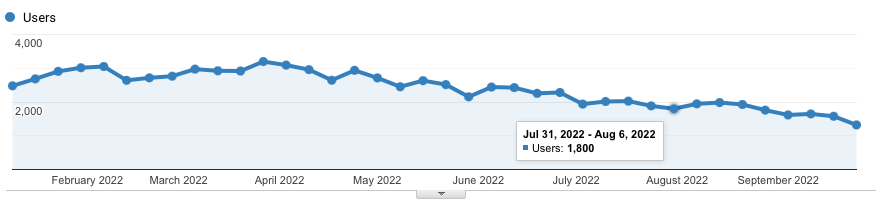

Here’s the same chart above, through the beginning of December 2022:

Ruh roh.

If you run a business and look at metrics, that graph probably looks pretty terrifying. And let me tell you, it was. By then, the big tech layoffs had spread pretty far and the numbers were getting much bigger.

Oracle: 200 people

Microsoft: 1,000 people

Stripe: 1,100 people

Meta: 11,000 people

SalesForce: 950 people

Amazon: 10,000 people

Cisco: 4,100 people

HP: 6,000 people

Amazon (again): up to 20,000 more people

The worst-case scenario that I had been a little worried about a few months earlier was actually coming true. Many of those are the companies whose new hires are my coaching clients. Amazon was the single-biggest driver of my business at the time.

To put a fine point on this: My business was built around these companies hiring new people. A “slowdown” would be a hiring freeze or just a reduction in hiring projections. This was a full on bottoming out: Not only were they not hiring, they were letting everyone go and the entire big tech employment market was seizing up.

People who otherwise would’ve been looking to make a move to a new employer were either being laid off or just sort of trying to keep their heads down, hoping to keep their jobs until the dust settled.

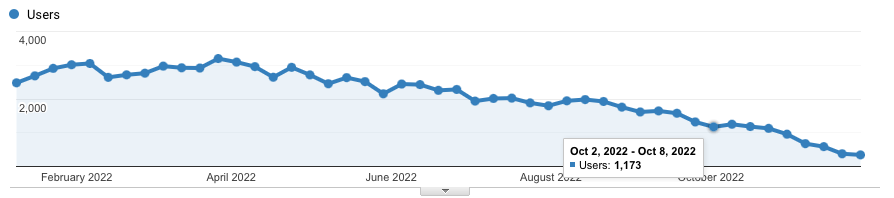

Here’s that same graph through May 2022 (the last full month before I write this):

This time, I have marked the week after I signed the contract on the new house. This is the week when I called a friend and said, “Something feels weird with the business.” It’s a month before the layoffs ramped up, but a month after my inbound traffic fell below the normal expectation for this time of year.

That same friend later said, “Your business was a leading indicator of trouble in the big tech hiring world. That’s remarkable.” It is pretty remarkable. I had dug so deeply into a particular niche that when it started to go south, my business immediately started trending down.

My revenue follows that curve. It’s now down 70-90% from last year’s revenue, depending on which month you look at.

A lifeline with Salary Negotiation Mastery

Just before all of the house stuff started, and before the business started slumping, I finally started working on a project I had been planning for a couple of years: Salary Negotiation Mastery.

It’s a self-serve program where I show the learner how to negotiate their job offer using the methodology I’ve developed over the past six or so years of coaching full time.

I had carved out a pretty narrow niche of people to work with one-on-one, and I was pretty busy with coaching for several years. So busy that I continually narrowed my niche to exclude a lot of people that my methodology would help. This way, I could continue working in my chosen niche and offer something for those outside my niche who wanted to negotiate with my help.

It was long overdue—I probably should’ve done this years ago—but I just didn’t have time to do it because coaching had been so busy. Ironically, I decided to just go for it and then the coaching business dropped off so I actually had lots of time to invest in making it really good.

This was fortuitous because it meant some extra revenue from pre-orders and early sales over the next several months. Forty percent of my Q4 2023 revenue was pre-orders for Salary Negotiation Mastery.

The main business driver for creating the program was that coaching revenue is very lumpy—one month can be fantastic and the next month can be terrible—because it’s a low-volume business. My result fee structure has helped smooth this out over the years by increasing overall revenue, but also just by nature of the lag from the end of each engagement until the payment of the result fee. It’s pretty random, which has a revenue smoothing function overall.

I finished building the program in January and launched it to get some more early sales. Now it’s in the “build a marketing funnel” stage, which is probably the thing I’m the absolute worst at in my business. But if I can figure out how to get it in front of the people who will benefit, then I think it could be a boon to my business.

This is just a working theory for why my business has fallen off

Before I transition to my plans to turn things around, I want to emphasize that my theory as to why my coaching business slumped so hard starting last September is that my chosen niche—Senior Software Engineers and Engineering Managers going to big tech companies—more or less evaporated when big tech companies starting laying people off instead of hiring.

It’s possible that theory is wrong and the business slumped for some other reason. If that is another reason, I don’t know what it is. But if I’m right, then the business is essentially dormant while big tech resets head counts to match the current economic situation.

So my working assumptions are: the business slowed down because my niche has temporarily gone away, the overall economy is actually very good in terms of hiring, and my current niche will come back … eventually.

The problem of course, is the word “eventually” is extremely vague and my runway has a pretty specific length. If there was a magic wand I could wave to understand if and when the current business will come back online, things would be much easier to plan out. But no such wand exists, so all I can do is make some educated guesses and plan for the most likely scenarios.

Where I’m going

So that’s where I am now.

What to do about it?

How and why I chose my current niche

Before we look forward, let’s look back. Here’s my current niche (described through my positioning statement):

I’m a Salary Negotiation Coach for Senior Software Engineers and Engineering Managers going to Big Tech companies like Google and Amazon

That has evolved over time.

How my coaching business started

My first-ever coaching client was a freelance copywriter who was transitioning into a full-time role. While I was writing Fearless Salary Negotiation, a friend reached out because he was negotiating a new job offer. Since I was writing the book, I offered to coach him pro bono so I could test my methodology and see how it held up in the real world.

It held up really well and my friend did well in his negotiation. Once the book was published, I sent him a copy since he had helped me vet the process that I wrote about.

A little more than a year later, his wife reached out and asked if I could help her negotiate. I told her sure, and she asked me what my rate was. I hadn’t really even considered coaching people one-on-one before this, so I didn’t have a rate to quote her. But she was a freelance copywriter, so I said, “Whatever your rate is, that’s my rate.” She said ok and we were off to the races.

We got a good result and I think we were both really happy with the experience. She sent over my payment and then I asked her why she had hired me even though she already had my book and her husband had been through the methodology with me.

“I just wanted you to tell me exactly what to do.”

This was a huge lightbulb moment for me. Even though she had a copy of my book and her husband had been through a negotiation using my methodology, it was still worth it for her to hire me and pay me to walk her through the methodology for her situation.

A couple months later, another acquaintance reached out and asked if I could help her negotiate her healthcare administration offer, and she asked what my rate was. I told her I could help and quoted a rate that was about 60% higher than the what I charged my first client. She instantly hired me.

Interesting. Another data point pointing to coaching as a viable option for my business.

Believe it or not, I was very resistant to this idea. When I began building the business (I was maybe six months in at this point), I planned to create a “passive income”-type business. I wanted to put products online, have people find them, and make sales without manual intervention, so one-on-one client work was more or less the opposite of what I set out to do.

Of course, I had a few friends who immediately said some version of, “You know… this coaching thing seems promising. That is a valuable service and I bet you could make a really good living with it.”

I happened to be attending a conference full of very smart people while I was working with my second-ever coaching client. The sentiment there was the same: This coaching thing could be really valuable. I also got some extremely valuable advice on how to structure the offering, price it, etc.

I went home and (still sort of reluctantly, if I’m honest) put up a landing page for my coaching offering. People starting hiring me pretty much right away.

My first positioning statement would have been: “Salary Negotiation Coach”. This is extremely broad because it implies “…for everyone.” That sounds great! “Everyone” is a huge market! But that’s not how business works.

Narrowing my niche

Still, folks were hiring me. Here’s a list of the types of clients I was working with as I wrote the book and for my first few paid engagements:

Software Developer

Software Developer

Healthcare Admin

Physical Therapist

Copywriter

Materials Engineer

Marketing Manager

Software Engineer

Software Engineer

Software Engineer

Software Engineer

Software Engineer

Software Engineer

You can see a trend develop right away. One of the first public speaking engagements I had was for a (now-defunct) coding bootcamp in Orlando.

Here’s a fun story that I don’t think I’ve ever told anyone. I spoke to this bootcamp twice. It’s a two-hour drive each way, and I was hoping to sell a few copies of my book to help cover expenses. The second time I went, I got a parking ticket that wiped out any profit I would’ve earned on those books. I was obviously doing this mostly for marketing purposes, but it would’ve been nice to at least break even on my costs.

ANYWAY, there was immediate interest for my coaching offering, and I inadvertently created some good content for Software Developers as “sawdust” from that talk. But other people were hiring me too, and from a wide variety of industries.

Eventually, I realized that a lot of Software Developers were hiring me and that Software Developers tended to get bigger results in nominal terms (they were being offered larger salaries and therefore an increase in their comp was worth more dollars).

I eventually decided to specialize and updated my positioning statement to:

“Salary Negotiation Coach for Software Developers”

Much narrower, but still very broad.

I started to build a reputation as the salary negotiation guy for software developers. More and more people hired me.

I noticed that more senior Devs were hiring me and they were getting even bigger results from our work together. I was getting pretty busy, and I realized that one thing driving my business was that my service was so cheap relative to the results I was getting for my clients.

Time to raise rates. I created a complicated pricing structure that was basically designed to charge more for folks with bigger job offers. It worked well enough, and my revenue per client started going up because I was capturing more of the value I created (even if I was doing it in a clunky way).

I eventually changed my fee structure to be simpler: A flat fee to work together (my service fee) and a percentage of the improvement we negotiated (my result fee). The business kept growing.

The Senior Software Developers were becoming the segment that got the most value from my coaching, and I was getting enough business from that segment that it made sense to update my positioning yet again:

“Salary Negotiation Coach for Senior Software Developers”

Narrower still!

Here are the next two iterations:

“Salary Negotiation Coach for Senior Software Engineers and Engineering Managers”

“Salary Negotiation Coach for Senior Software Engineers and Engineering Managers going to Big Tech companies”

You can probably see how these changes happened: I had more than enough work to make a living and the data told me those were the folks benefiting the most from my coaching offering.

This is also a pretty narrow niche (though still huge in terms of the total addressable market).

The benefit of having such a narrow niche is that when those people find me, they know I’m their guy. I’m very specifically describing a group of people which sends a powerful signal that I can help them (especially with all the testimonials I’ve accumulated over the years).

There’s also one huge downside: If that narrow niche hits any economic speed bumps, so do I (see above).

It has always felt restrictive

I think that narrow niche was the right thing to do as I worked to build my business and establish a brand.

But it felt pretty restrictive from the start, and continued to feel more and more restrictive.

I kept narrowing my niche for two reasons:

- I could see who was benefiting from my help.

- I wanted to work in the highest-leverage situations I could.

I’ve always had an application as the first step for any coaching engagement. The application has been pretty much the same since the beginning (with a few small tweaks here and there).

When I first started coaching, and realized how good Software Developers’ results were, then I would always review a new application by looking straight to the “What is your line of work (industry and job)?” question. I wanted to see “Software Dev” or something like that. Later, I would hope to see “Software Dev” paired with “tech” or “big tech”.

Then I would look at the “What stage are you at in the job hunting process?” question. I was hoping for “Job offer in hand”.

Why?

Those were the clients who got the best results and therefore got the most value from my coaching. And “job offer in hand” meant their need for my help was the most acute; they urgently needed my help. Since my fee structure is based on the value I create, that meant more revenue for the business.

Over time, I began to scan the applications differently. Instead of “industry and job”, I would first look at “What’s the annual compensation of your offer?”. I had to be selective about who I worked with because I only had so much bandwidth, so I started looking for folks with higher compensation to work with and hence higher potential result fees.

Since more-senior folks tend to get bigger job offers, I started to evolve my positioning.

I called it “moving up the org chart”. The higher up the org chart, the better the pay and the more leeway to negotiate.

In addition to “these folks get more value from my help”, this was the main driver for my continually-narrowed positioning. I was trying to manage demand for my service while staying within the niche I had carved out, so I moved up the org chart through a series of positioning-narrowing moves.

Conventional wisdom is that a narrower niche is easier to cater to because it’s so specific. Basically, the more specific a persona I need to market to, the easier it is to speak in a way that resonates with them.

But I felt very restricted by this.

I think that’s mostly because I was using job title and type of organization as a proxy for the thing I was actually optimizing for: income. The bottom line is I only have so much time to invest in helping my clients, and I need to use that time in the highest-leverage way possible. But I also want to help as many people as possible. It’s a Catch-22 in some ways.

So once the big tech slowdown happened, I had to start thinking deeply about my business, whether it continues to be viable, and who I can help.

Then I had an epiphany (which will hopefully seem obvious to you by now)…

How and why I’m choosing a new niche

Why don’t I just directly work with the folks I had been trying to find by proxy over time?

The conventional wisdom when starting a business is that you choose a narrow niche because it’s easier, cheaper, and faster to iterate and build in a niche. It’s much easier (or cheaper, at least) to start a new company that specializes in making the world’s best athletic socks than, say, a general apparel company. The questions you’re asking that early are things like, “Who wears athletic socks? How do we find them? What do they look for in a good sock?”

That’s pretty narrow, but it might be even easier to start with “men’s athletic socks” or even “men’s tennis socks” because the questions get more and more specific and easier to answer.

If that company starts super broad, they have to answer questions like, “Who wears apparel? Where can we find them?” When you’re just starting out on a shoestring budget and you’re planning your product development and early marketing plans, these answers to these questions (“Everyone!” and “Everywhere!”) are not useful or budget-friendly.

But it’s also true that as businesses grow, they expand—either horizontally or vertically—to serve other niches or simply expand their chosen niche.

“We’re going to sell the world’s best athletic socks” is a narrow-ish niche. And if that company succeeds, they start to realize things like, “Hey. You know what? We’ve gotten pretty good at designing socks, sourcing materials and manufacturing them. How different are t-shirts from socks? We could probably do that too, right?” They expand their scope to leverage the expertise they’ve accumulated over time.

This happens constantly and usually sounds like this at a dinner-table conversation:

“Where’d you get that shirt?”

“ACME co. It’s new. You like it?”

“ACME co.? The yoga pants company?”

“Yeah, they’re selling men’s casual apparel now too.”

“Huh.”

This is called “economy of scope”, which is a cousin to “economy of scale”.

They already have designers on staff, know how to source materials, how to negotiate contracts with a manufacturing facility, they have distribution, and so many other things that are needed for the new products, so why not expand into t-shirts?

My new positioning statement

In my case, I already have a methodology that works really, really well in my chosen niche. And I know it works well in a broader niche (people higher up the org chart). Why not expand my niche?

Which leads me to my new positioning statement:

I’m a Salary Negotiation Coach for high earners

I’m a huge fan of “alignment of incentives” and this is similar. For the past few years, I had mostly been trying to work with high earners, but I was doing it through a side door, which made a lot of new-client intro calls more difficult than they needed to be.

Half of my clients over the past 18 months were not “Senior Software Engineers or Engineering Managers”. They hired me despite my positioning statement, not because of it. And I was able to help them get great results.

It’s impossible to know this, but I suspect there were many more folks who would’ve considered working with me, but they self-selected out since they were not described by my positioning statement.

My new positioning statement is an umbrella covering my previous niche

The best part is my previous niche is still perfectly covered with my new positioning statement. Those folks were almost all high earners.

That’s the high-level benefit. But there’s a lower-level, tactical benefit too: All of my current marketing and collateral is still useful for those folks. The landing page, emails, scores of podcasts I’ve been on, articles on my site, and everything else I built to help those folks will still be just as helpful to those folks.

That’s also true for my coaching offering—it will continue to be just as valuable to Senior Software Engineers and Engineering Managers going to Big Tech companies as it was before. And when big tech hiring stabilizes, I’ll be there waiting to help those folks negotiate their job offers.

But meanwhile, I’ll also be helping high earners in other jobs and industries, just like I have been. But now those folks—the high earners who might have previously seen my positioning and thought, “Oh, that’s not for me.”—will feel that my coaching service could be right for them.

Timing is everything

This probably would not have worked when I first started the business. When people hire me, they don’t know who I am so I rely on a lot of credibility-building proxies to help them trust that I know what I’m doing.

For Software Engineers, I had one very nice built-in indicator that I could help them: I am a software engineer. Same for Engineering Managers: I was a people manager. I added “going to big tech companies later”, but only after I had worked with many folks going to big tech companies.

Over time, I built more credibility such that those folks hired me and continually trusted me with more and more valuable negotiations. Eventually, virtually all of my clients were also “high earners”, but it didn’t start that way. And if I had just started out with a focus on “high earners”, I would’ve had a bear of a marketing problem.

What about Salary Negotiation Mastery?

The beautiful thing about this move is it only increases the potential reach and value of Salary Negotiation Mastery. Here’s the short version:

My salary negotiation coaching offering is for high earners who need help negotiating an offer right now or in the next couple of weeks.

Salary Negotiation Mastery is for folks who are not yet high earners but want to be, or who simply don’t have the budget for my one-on-one coaching offering, or who are looking ahead and want to be prepared for future job offers and negotiation opportunities.

Salary Negotiation Mastery is also a great way for folks who don’t know me to get to know me without a formal engagement so they can decide if salary negotiation coaching is right for them down the road.

I have been looking into potential partnerships that would enable me to work with other folks whose audience might benefit from Salary Negotiation Mastery, but it has been challenging because of my current positioning. “Will this work for non-engineers?” is a question that virtually every potential partner asks. “Yes!” is the answer, but it takes a while to explain that.

Now I won’t have to explain it.

“Will it work for folks who are not yet high earners?”

“Yes!”

“Will it work for [specific industry]?”

“Yes!”

That’s all there is to it. Easy.

What’s next

Now I have a new positioning statement. Ironically, that was the easy part (even though it was really, really difficult to make this decision) and this is when the hard work begins.

The list is long and ranges from “update entire website” to “change twitter bio”.

I have to rework the Fearless Salary Negotiation website (which I have been quietly doing behind the scenes for the past month or so anyway). I need to write some new landing pages. I have to update a whole bunch of email sequences.

And I have to start answering that difficult question, “Where do I find high earners who have job offers to negotiate so I can help them?”

But! Those people are already finding me and (I think) walking right by the store because my previous positioning statement didn’t appeal to them. So my first task is to just make sure the people who are already finding me know they’ve come to the right place. That’s actually pretty easy: Update a few pages on my website and write a new coaching page.

I’m working on that now. (Well, not now because I’m apparently writing a short book about my new positioning, but next.)

How you can help

If you’ve read this far, first of all, thank you for your time.

I had no idea this post was going to be this long, but here we are. As you read, my business has been more or less dormant for about nine months and I’m hoping this new positioning will kickstart it.

If any of these things are in your wheelhouse, I’d be grateful for your help:

- If you know any high earners (more than $200k income per year) who are changing jobs soon, please tell them about my salary negotiation coaching service. Referrals are my most important way to find new clients to work with.

- If you know someone who has an audience of high earners, I would love to meet them and talk about ways I can share my salary negotiation expertise with them. This could be a podcast guest appearance, an article on their site, or any number of things with a focus on adding value to their audience. Would you please ask them to get in touch?

- If you read the previous two and thought, “Well, I know folks Josh could help but they’re not high earners … yet.” Would you tell them about Salary Negotiation Mastery? It’s a fantastic program and it will help them get the maximum compensation next time they negotiate a job offer.

Thank you again for reading this. I think it’s extremely important to document big changes like this because it helps me remember what I did and why I did it. It also helps me avoid falling prey to any number of logical fallacies that are easy to succumb to in the moment.

There’s also a tendency for entrepreneurs to write about their wins and gloss over the hard times. Entrepreneurship is hard and I think it’s a disservice to aspiring entrepreneurs to hide the difficult parts. I’ve fought to avoid that since I started my business and I’m not going to start leaving out the tough stuff now.

I hope I can write a glowing update in a few months or a year, but that’s absolutely not a certainty. If this doesn’t work, I’m not sure what I’ll do. For now, I’m laser-focused on making it work. Wish me luck!